BLOG: APPLIED RESEARCH OF EMMANUEL GOSPEL CENTER

Exploring Church Spaces

Christians look on in dismay as empty churches are converted into luxury condos, but congregations are beginning to reassess how their sacred spaces are used outside Sunday worship.

Christians look on in dismay as empty churches are converted into luxury condos. Steeples used to dot city skylines and dominate small towns. But for decades now, it’s felt like these sacred spaces are being overshadowed. Disemboweled.

However, a sea change is underway as congregations reassess the use of their buildings outside Sunday worship. They are beginning to ask themselves some uncomfortable questions: How much of our building lies empty during the week? How much dead space is the church creating on a city block? How else could this space be used? Who else could benefit from this space?

Communities and cities are buckling under the strain of challenges such as affordable housing, economic and education inequality, mental health and substance abuse, environmental resilience. There is a unique opportunity for churches to leverage their real estate assets for missional witness.

Saranya Sathananthan, a researcher in residence at EGC, has been engaging with local congregations at the forefront of church-space innovation. She delves into the challenges they face and uncovers powerful missional opportunities in reimagining church spaces.

Explore the resources she and her team have created and discover insights on church-space innovation.

Challenges and Solutions for Maximizing Church Spaces in Boston

While many churches in Boston share their space with congregations, nonprofits, or community members, several barriers prevent them from fully utilizing their properties for mission.

Challenges and Solutions for Maximizing Church Spaces in Boston

by Saranya Sathananthan, Researcher in Residence

One of the main observations from this study is that most of the churches that participated were well-aligned when it came to utilizing their property for mission. It should come as no surprise, given that numerous churches in the city rent to other congregations, provide office space for nonprofits, or allow community members to host events for nominal fees.

While this represents a great strength in how churches utilize their properties in Boston, it still represents only a fraction of what could be happening. (See this list of innovative uses of church spaces.) Despite this potential, several barriers prevent churches from fully utilizing their properties for mission.

Vision and Mission

A key indicator in determining how open a congregation is to creatively using its property lies in the theology of its senior leaders regarding sacred space and stewardship. The research revealed that leaders with a broader understanding of stewardship often cast a vision for their congregation that embraced opening their buildings to the rest of the community for purposes beyond worship services. Some leaders saw the church building as a tool for ministry, expressing a desire for it to bless the surrounding community. Others shared their perspectives on the sacredness of a building itself. While some expressed that the architecture or history of their building drew people to the church, leaders who viewed the physical structure as "just a building"—with the sacredness residing in the people and activities where God's presence is invited—tended to foster a more flexible, community-focused use of their spaces.

However, some leaders experienced notable tension when they tried to shift their congregation's mindset about property use. Some expressed that their church's subculture leaned toward risk aversion, with worst-case scenarios prompting people to want to close their doors and retreat into enclaves rather than serving as launching pads for their communities. In other contexts, leaders noted that specific subgroups, having worked hard to secure their space, were highly protective of their resources. They feared that opening their doors could lead to misuse or loss, which made them hesitant to fully embrace the potential of their church property to serve a wider group of people.

Aging Infrastructure Against Limited Funds

One of the most pressing issues facing many Boston churches is the undeniable reality of aging infrastructure. Over 50 churches in the city are registered as historic landmarks, and many church buildings, regardless of these official designations, are old and need significant repairs. Unfortunately, the funds required to address these issues are often limited, particularly for smaller, dwindling congregations that struggle even with the regular upkeep of their expansive historic buildings.

This issue is not unique to Boston; it mirrors trends in other major cities and Western nations. In the United Kingdom, over 2,000 church buildings have closed during the past decade.1 In New York City, more than three dozen houses of worship and similar buildings were razed or redeveloped in Manhattan alone between 2013 and 2018,2 often replaced by high-end condos. Each year, congregation closures outnumber new church starts in the U.S. by 50%, according to Lifeway Research. In 2019, prior to the pandemic, although about 3,000 new Protestant churches were planted, 4,500 Protestant congregations closed. In Boston, over recent decades, about 45 buildings owned by churches have been lost to the Christian community, primarily through sales to developers and private commercial entities.

Another aspect of this challenge is that many church buildings in Boston are not fully accessible, up to code, tech-equipped, or readily transformed for different needs. Moreover, historic designations restrict how churches can renovate many of these buildings. These limitations hinder churches' ability to serve their communities effectively, particularly in welcoming people with disabilities or hosting events that require modern amenities. A combination of even a few of these conditions can significantly limit how the space can be used, preventing churches from fully utilizing their buildings for diverse activities or adapting them to meet modern needs. Notably, many churches participating in this project had fires that rendered certain spaces of their churches unusable for years before repairs could be made.

“Do churches spend their limited resources on maintaining or updating their buildings, or should they abandon ownership and focus their funds directly on ministry activities?”

The cost of bringing these buildings up to current standards can be prohibitive, particularly for congregations already struggling financially. The cumulative effect of deferred maintenance leading to more significant issues has resulted in many churches closing, with buildings left abandoned,3 sold, or even demolished.

This situation presents a dilemma for many pastors: Do churches spend their limited resources on maintaining or updating their buildings, or should they abandon ownership and focus their funds directly on ministry activities?

"We sold our former building for a very good price, but now the question is, shall we use it on brick and mortar?” Pastor Daniel Chan of Boston Chinese Evangelical Church in Boston’s Chinatown said. “Our deacons are raising the question of whether we should spend the money on ourselves (on a new multifunctional sanctuary) or spend the money directly on the community. So we are still struggling and debating."4

Limited Leadership Capacity and Training

Limited leadership capacity in many congregations further complicates their decision-making regarding church infrastructure. Pastors and church leaders are often stretched thin, balancing their congregations’ spiritual needs with the practical demands of maintaining their facilities. Many seminaries do not provide pastors with practical education on facilities maintenance or the business acumen needed to run a church, leaving leaders to learn on the job.

“The main challenge is inexperience, just not knowing what we're doing for a lot of these things,” Pastor Larry Kim of Central Square Church in Cambridge, Massachusetts, said. “There's always a new surprise here in this building, and it's trying to figure out how to problem-solve those things. It’s like I'm learning things for the first time.”5Although some denominations have long provided practical support for church operations, facilities management, and loans for repairs and upgrades, we are now finally seeing a broader range of resources and services that better equip leaders with the knowledge they need becoming available.

“There's no lesson like on-the-job training,” Pastor Kurt Lange at East Coast International Church in downtown Lynn, Massachusetts, said. “But there are now books written by Christian authors and church leaders in this space that I do think a lot of pastors need to read.”6Pastor Kurt Lange's Recommended Reading List

Delegating facilities management and related responsibilities to non-pastoral roles can benefit churches with the capacity to hire staff or manage volunteers. However, this may not be feasible for smaller churches with limited internal resources. Whether the church hires staff or enlists volunteers to assist with facilities management, make repairs, write grants, or take on other specialized roles, investing in the professional development of these staff members and volunteers is essential. If church leaders don’t learn what is needed, others cannot be expected to know this information, even if they bring relevant skill sets to their roles. Each church situation is unique, and the number of intersecting decisions to be made at any given time makes it challenging even for the most trained or experienced professionals. Churches that understand the value of investing in their leaders are more likely to succeed, and recognizing those who manage and maintain the facilities as essential to the church will contribute to its overall success.

“If we want to help our staff members to be successful, we need to provide training for them,” Pastor Chan of Boston Chinese Evangelical said. “Our facility manager needs training on property management, our technician needs training to develop skills to make repairs, and we realized that we may need to put more money into training even our pastor, who is coordinating all this. He didn't study this in seminary. So we realized we need a budget for training our people.”Even if a church lacks the funds to hire staff, outsource services, or send people for professional training, sharing knowledge within the congregation can be a valuable way for everyone to contribute to the overall vision. Tapping into the expertise of individuals who can teach or offer specific skills and “doing it together” can foster shared experiences that build missional solidarity.

“Find out who your people are and what they know. Include everybody in your parish, because there’s all kinds of good ideas out there.”

“Find out who your people are and what they know. Include everybody in your parish, because there's all kinds of good ideas out there,” Jim Woodworth, facilities manager at the Cathedral Church of St. Paul in downtown Boston, said. “But sometimes you’ve got to draw them out of people.”7

“Some of my people aren't in the workforce,” Pastor Lange of East Coast International said. “So we’re teaching people how to paint, hold a drill, etc., for people who have never had a chance to do it.”

He shared that the sending church they came out of would have hired a company to make any necessary repairs or do construction, but that they were not at a place where they could afford it when they were a church plant. Though their circumstances have changed since then, he still emphasized the need to think through whether to hire an outside company.“Sometimes just because it may be easier for us to pull it off, or faster, or better, we have learned that there are some real interesting discipleship opportunities in working with people, like doing manual labor together.” Pastor Lange said. “So we kind of enjoy it—working with people in that capacity.”

An observation from the research revealed that when an entire congregation is committed to the vision for the church building, there’s more significant motivation for everyone to contribute. It is the task of church leadership to communicate that vision effectively, from the leadership level to every person in the congregation and beyond or cultivate that vision together through a series of discussions that brings together various stakeholders. This process is vital, whether the church has abundant or minimal resources for the upkeep of facilities.Take Congregación León de Judá in the South End neighborhood of Boston, for example. Under the direction and vision of Pastor Roberto Miranda, the congregation purchased a building in the South End in 1994 and undertook a decade-long renovation, with members volunteering their time and skills and resourcing supplies to build the church.

Javier Encina, the facilities manager at León de Judá, described church teams tearing flooring from homes and putting it back together in that building, almost completely fitted with donated materials.“It took us around 10 years, between volunteers and salvaging materials and reusing them, to build this church,” Mr. Encina said. “We built this building with the sweat of the people. All the work and manual labor on the church was done by the people of this church.”

No wonder this hallmark congregation takes deep pride in their building and invests in its upkeep, ensuring it remains a welcoming place for their members and the broader Boston community.

Figs. 1-4 Members of Congregación León de Judá work together on reconstructing the Harrison building, the first building they purchased in the South End. Figs. 5-6 Hallway and entrance to the Harrison building. Photos courtesy of Congregación León de Judá.

The Difficulties of Decision-Making and Management

Effective decision-making regarding the use and maintenance of church properties is often complex and challenging. Many churches have governance structures that can slow decision-making, leading to frustration and burnout among those responsible for managing the property. Establishing a dedicated team to handle property management can alleviate the burden on pastoral staff, but this requires careful planning and clear communication.

Deciding to expand the use of church space introduces new challenges. Questions arise, such as who will open the space, manage access, troubleshoot issues, ensure security, handle cleanup, and deal with inevitable wear and tear. Churches may need to consider growing their team and delegating additional leadership responsibilities.Moreover, churches often face bureaucratic obstacles from the city or state when adapting their spaces for new uses, particularly regarding regulations for activities involving minors or other vulnerable populations and the need to obtain special permits. When a church transitions to additional usages, even adding a single one could elicit numerous issues. These challenges can be daunting and may discourage churches from moving forward if not carefully considered. Every church I interviewed expressed these challenges when opening their space for additional use beyond Sunday services.

Helpful Mindsets and Postures

When asked how they navigate these challenges, several leaders shared helpful mindsets they adopt.

"I expect things to go wrong. I expect to have to switch gears constantly. We prioritize, and then we re-prioritize. But that's the job."

— Jim Woodworth, facilities manager at the Cathedral Church of St. Paul in downtown Boston, on the need for flexibility

“Be nimble and pivot.”

— Laura Mitchell, Director of Children and Youth, from Central Square Church in Cambridge, MA, reflecting on the challenges with their building’s heating. They had to rearrange everything and move from the sanctuary to the fellowship hall for a few months.8

“Lead with patience. We have to be mediators, understanding everyone’s point of view."

— Yulieth Ramos, the administrative assistant at Congregación León de Judá in the South End neighborhood of Boston, describing how she manages the frustrations of staff or members when a group leaves a mess after an event9

“You’ve got to be willing to be innovative and entrepreneurial. What has helped our church is avoiding the mindset of 'we've always done it this way' or 'we've never done it that way.' … Maybe God is trying to move flexibly with us, but we're staying rigid, not allowing God to do what He’s trying to do. That flexibility is tied to good stewardship—managing things properly, responsibly, ethically, and justly."

— Pastor Darrell R. Hamilton II of First Baptist Church of Jamaica Plain in Boston, on the value of innovation and the need for flexibility10

For churches who share their space with other groups, it’s also crucial to be aware of cultural differences and power imbalances between host and guest and how they can impact relationships. EGC conducted research on congregations sharing space in 2012 and section three and four of this blog post on Shared Worship Space11 has additional factors to consider when sharing space where there are major cultural and economic differences between the hosting congregation and groups that share their space.

People, Processes, and Communication

Many pastors emphasized the importance of the right processes and people in overcoming challenges.

"I don’t know what I’m doing half the time," Pastor Christina Tinglof of Forest Hills Covenant Church in Boston, admitted. "I would say to other pastors: make sure you’re not making decisions on your own. It’s important to involve others."12Pastor Hamilton echoed this sentiment, stressing that "cultivating a good team is critical."

“Cultivating a good team is critical.”

When things don’t go as planned, Pastor Lange of East Coast International shared their approach to handling issues with outside groups that use their space: “We make sure to maintain a benevolent attitude towards other churches that use our facilities, but that requires us to have quick conversations whenever something goes wrong.”

Establishing clear internal processes and communicating space usage guidelines to everyone involved takes time, often requires trial and error, and can be frustrating—just like any growing pains. Each church's processes and policies may need to adapt during different seasons of change and transition.

The most significant takeaway from leaders' experiences in successful property management is the importance of pacing. Churches don’t need to do everything at once. It’s often better to start with small, manageable changes, learning from those experiences before expanding further. This iterative, flexible approach allows churches to refine their processes and avoid being overwhelmed by the demands of managing an active, multifunctional space. Trying something new might sometimes feel like taking one step forward and five steps back, but having the resilience to address setbacks before moving forward is critical to long-term growth and sustainability.

“It cannot be one size fits all.... We have to work with the moment.”

One fascinating observation from my conversations with church leaders was the contradictory nature of the advice they offered. One person would recommend having a single administrative person manage all scheduling online, while another said they’re OK with multiple pastors managing the schedule without an online calendar. A few advocated strongly for outsourcing repair work, while another made the case for involving volunteers from the church. Some pastors advise being deeply involved in management details, while others recommend delegating those tasks. These different approaches taught me early on that there’s no single solution. Each church should take inventory of its strategies, weigh the pros and cons, and decide what works best, then reassess and adapt as circumstances change.

“It cannot be one size fits all,” Pastor Marc Lefevre of Boston Missionary Baptist Church in Roxbury, Massachusetts, said. “Based on who we are, we can do it this way. Yet when we become bigger, it would be impossible to do it the same way. When we were only 15, or when we were only 100, that was a different ballgame. But now that we are a growing church, you have to do things differently. We have to work with the moment.”13

- Rachel Pfeiffer, “After 2,000 UK Church Buildings Close, New Church Plants Get Creative,” Christianity Today, May 25, 2022, https://www.christianitytoday.com/2022/05/uk-england-church-close-anglican-buildings-restore-new/.↩︎

- C. J. Hughes, “For Churches, A Temptation to Sell,” New York Times, October 4, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/04/realestate/for-churches-a-temptation-to-sell.html.↩︎

- Matthew Christopher, “Why Are There So Many Abandoned Churches: Changing Neighborhoods, Loss of Faith, Even Heating Bills Make Places of Worship Among the Most Common Types of Forgotten Places,” Atlas Obscura, February 29, 2024, https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/abandoned-churches.↩︎

- Daniel Chan, interview by author, September 20, 2023.↩︎

- Larry Kim, interview by author, October 11, 2023.↩︎

- Kurt Lange, interview by author, November 3, 2023.↩︎

- Jim Woodworth, interview by author, September 29, 2023.↩︎

- Laura Mitchell, interviewed by author, October 11, 2023.↩︎

- Yulieth Ramos, interviewed by author, August 30, 2023.↩︎

- Darrell R. Hamilton II, interviewed by author, February 22, 2024.↩︎

- Bianca Duemling, “Shared Worship Space - An Urban Challenge and a Kingdom Opportunity,” Emmanuel Research Review reprint Issue No. 74, January 2012, https://www.egc.org/blog-2/2012/1/16/shared-worship-space-an-urban-challenge-and-a-kingdom-opportunity.↩︎

- Christina Tinglof, interviewed by author, November 2, 2023.↩︎

- Marc Lefevre, interviewed by author, November 10, 2023.↩︎

Opportunities for Leveraging Church Spaces

Churches open to reimagining how their spaces can be utilized may discover new ways to serve their communities, build stronger connections, and contribute to the financial sustainability of their facilities.

Opportunities for Leveraging Church Spaces

Finding a Sweet Spot: Missional Alignment, Financial Sustainability, and Community Vitality

by Saranya Sathananthan, Researcher in Residence

Churches open to reimagining how their spaces can be utilized may discover new ways to serve their communities, build stronger connections, and contribute to the financial sustainability of their facilities.

Mission-Driven Space Utilization

One key opportunity many churches are already embracing is evaluating and repurposing underused spaces for mission-aligned activities that benefit the community. They are partnering with local organizations, offering space for community events, or creating new programs that address the surrounding neighborhood’s needs. By aligning the use of space with their mission, churches can ensure that the use of their properties is furthering their spiritual and community goals.

Mathew Jarell from the Cathedral Church of St. Paul in downtown Boston spoke to the challenges and rewards of utilizing space for mission-aligned activities that serve different groups and purposes. The cathedral has only one large sanctuary that it adapts for use by different worshiping communities, musical events, and meetings.

“Space doesn’t just morph into whatever is needed; it requires a lot of preparation, hard work by our facilities team, and time and energy.”

“It takes a lot of planning,” Mr. Jarell said. “Space doesn’t just morph into whatever is needed; it requires a lot of preparation, hard work by our facilities team, and time and energy. But we’ve made things possible.”1

Given their context in downtown Boston, where space is at a premium, he shared how their church space has supported people planning events there.

“When we get a request from a group planning an event on the Common, it feels good when we can help. It feels like we’re contributing to the life of the neighborhood and the city,” he said “It’s challenging, but it’s really rewarding and a great, great opportunity to be able to be a part of that.”

Innovative Use of Church Spaces

Another opportunity lies in reimagining what’s possible with church spaces. This page includes a list of possible spaces in church buildings or on church-owned property and an expanded list of potential uses in urban contexts. These ideas stretch the imagination, showcasing what’s possible—from indoor play areas for families with young children to urban farms on rooftops or lawns.

Some churches are already finding creative ways to use their buildings, from hosting coworking spaces to providing affordable venues for arts and cultural events. By adopting flexible and adaptive-use policies, churches can respond to the dynamic needs of their communities and explore new ways to generate income while staying true to their mission.

Fig. 1 The Loft at Stetson is a thrift store owned and operated by East Coast International Church which doubles as a location for on-the-spot counseling. Proceeds from the thrift store go toward a church ministry that supports women in recovery.

Pastor Kurt Lange from East Coast International Church in Lynn, Massachusetts, discussed using their spaces for multiple purposes. The lobby of their church also serves as a cafe, which is open Monday through Friday, with the church using it on nights and weekends. They doubled up their church offices with the nonprofit they started. The second floor of another building is a thrift store, which also serves as a counseling center.

“We’re very comfortable organizationally with the messiness of there being a worship space that is also a cafe that’s also a job training center that is also a space for community meetings.”

“We're very comfortable organizationally with the messiness of there being a worship space that is also a cafe that's also a job training center that is also a space for community meetings, and we could just keep going,” Pastor Lange said. “So everyone knows that you don't really know what you're going to walk into on any given day unless you look at the calendar.”2

Fig. 2 Land of a Thousand Miles Coffee owned by East Coast International Church. The coffee shop is also the front entrance and lobby to their main church sanctuary.

Economic Impact on the City

"The average historic sacred place in an urban environment generates over $1.7 million annually in economic impact,” a 2016 research study conducted by Partners for Sacred Places found.3 This impact stems from churches offering jobs and training individuals; purchasing goods and services from local businesses; serving as incubators for nonprofits and small enterprises; and providing affordable spaces for life events, from weddings to funerals.

Given this substantial contribution, this moment calls for civic leaders in Boston to invest in revitalizing church spaces, expanding their role and service as community hubs. As more churches face financial pressures that force them to close or move and sell their properties, the city risks losing institutions that provide invaluable contributions to its residents.

The implications for the vitality of Boston’s neighborhoods are significant. The loss of a church can mean the loss of accessible, affordable space for various activities and the elimination of a vital gathering place where people build social capital and access a wide range of often free programs and services that enhance individual lives and the community.

“If our church closed down, would anybody notice?”

Several church leaders emphasized this vital role. Pastor Davie Hernandez of Restoration City Church in Roxbury, Massachusetts, asked his congregation: “If our church closed down, would anybody notice? We have to be a church that, if we miss one day, everybody's asking what happened. That's what we strive to be. We want to be so much a part of the community that we are part of the lives and livelihood of everyone in our community, part of a system or the ecology of their daily lives.”4

Boston’s churches, often situated at central locations within their neighborhoods—at major intersections or on main streets—offer a unique opportunity for community impact. These churches typically share the goals of local nonprofits, possess ample underutilized space, and provide various facilities, from kitchens to auditoriums.

Historically, they have also been deeply rooted in the spiritual, social, and cultural lives of their communities. Even a modest investment to help a church maintain its building assets or adapt to a new use that benefits the community could have a significant and far-reaching impact.

In light of the city's needs, there are unique opportunities for churches to partner with civic leaders, developers, nonprofits, and other stakeholders to further Boston's economic empowerment and vitality. Churches can leverage the underutilized spaces in their buildings for use as commercial kitchens, early childhood education such as daycare centers and schools, affordable housing, and spaces for the arts.

Community Hubs & Cultural Centers

Beyond the economic impact, churches also have the potential to serve as vibrant community hubs and cultural centers, addressing a wide range of local needs. This opportunity allows churches to expand their role beyond spiritual nourishment to include social, educational, and cultural engagement. Some churches have successfully transformed their properties into dynamic community centers offering various services, from food pantries and after-school programs to cultural events and neighborhood meetings.

In many immigrant communities, churches naturally serve as cultural centers where the congregation and the community are deeply intertwined. These churches often provide spaces where people can connect with their cultural heritage while meeting practical needs. For example, a church might offer language classes, legal aid, or job training programs specifically tailored to the needs of their community members. This dynamic was evident in many diasporic churches I interviewed in Boston.

Congregación León de Judá in the South End neighborhood of Boston houses Agencia ALPHA, a well-established immigration service in Boston. When I visited, the building was bustling with activity, with several staff members taking phone calls and interns working to support the team.

Fig. 3 English class in progress at Boston Missionary Baptist Church. Emmanuel Gospel Center.

Boston Chinese Evangelical Church in the Chinatown neighborhood of Boston and Boston Missionary Baptist Church in Roxbury, Massachusetts, offer English classes to their diasporic communities. These programs are open to the community, regardless of whether participants are congregation members.

Pastor Daniel Chan of Boston Chinese Evangelical Church said this aligns with their church's vision because the majority of their members are first-generation immigrants.

“When we first immigrated to America, we struggled with English, finding jobs, and other difficulties,” he said. “But after 30 years, we’ve been able to settle down. Most of us now have jobs, and some even own homes.”5

While many of their members have moved to more affordable areas like Qunicy, Malden, and other Chinese population centers, new immigrants are still coming through Chinatown.

“That’s why we decided to stay in Chinatown—to be a blessing to the community,” Pastor Chan said. “We have after-school programs, community English classes, and summer camps for middle school students. This church still pulls people back to the community to help. We want them to remember that they were once immigrants, and now that God has blessed them, it’s time to give back. Our vision is: ‘Blessed to be a blessing to others.’”

Fig. 4 Friday Food Pantry Distribution at Boston Missionary Baptist Church. Emmanuel Gospel Center.

Pastor Marc Lefevre of Boston Missionary Baptist Church said the church uses its space to provide community services such as computer and English language training, food distribution, and immigration support.

“We are open to the community—many local organizations use our space for their meetings or gatherings,” he said. “They know it’s open for them. We don’t charge for the space; we see it as a blessing from the Lord.”6

This idea of the church as a community hub extends to all who enter its doors, whether they are members of the congregation or people in need. When churches embrace this role, they become places of refuge, support, and connection for the entire community. The 2016 report by Partners for Sacred Spaces found that "87% of the beneficiaries of community programs and events housed in sacred places are not members of the religious congregation. In effect, America's sacred places are de facto community hubs.”7

This has been especially true for Black churches which have played a critical role in the formation and maintenance of Black life in America for centuries. In Boston, churches have been the heart of movements that have advanced human and civil rights from abolition in the 19th century to anti-violence organizing in the 1990s. A combination of historical, social, and economic factors has led to significant displacement of Boston's Black community which has had a profound impact on churches, particularly in their role as social and cultural centers. This displacement has challenged Black churches' ability to maintain their central role in fostering community cohesion, cultural identity, and social services, while also pushing them to adapt and advocate for the preservation of their communities amidst gentrification and economic pressures.

Examining Who is Inside & Outside the Church

As churches continue to function as crucial community hubs, one question arises: Who do you find inside and outside the church, and are they one and the same? Does the congregation reflect the community? Suppose your local community includes people experiencing homelessness. How can the church’s offerings holistically include not just spiritual nourishment but also practical services such as a free or subsidized laundromat, showers, haircuts, and access to housing—making the church a genuine, welcoming place for them to belong? How can the utilization of church space contribute to a closer integration of the congregation and the local community?

While churches can serve as community hubs, it's crucial to establish clear boundaries on how people use the space. A church’s space does not need to become everything to everyone, and it's important to communicate this to both the congregation and the broader community.

“Who do you find inside and outside the church, and are they one and the same? Does the congregation reflect the community?”

I discussed the challenge of setting boundaries around the use of church space with Yulieth Ramos from Congregación León de Judáh in the South End neighborhood of Boston. When I asked how she would respond to people who believe the church should be open to anyone at any time because of its role as a sanctuary, she said the church is responsible for stewarding its space well for the sake of all who use it.

“What I said to one person who asked me that question was, ‘I understand that the church is open, but we have to take care of the space because we're using it every day,’” she said. “Even if someone wanted to stay overnight, we would have to do so much to ensure that this space remains safe in the evenings and still usable by the other people who share it during the day. While we are a church and we do want to help, we're not a shelter, and if someone needs one, we can help them find it. We have to set boundaries to ensure this place remains safe and accessible by all the groups that use it.”8

Churches are encouraged to stay true to their mission and vision while remaining flexible on implementation. Some congregations experience mission drift as they begin to evolve into nonprofits. One way to maintain a distinction between these roles is to establish separate entities and management to ensure that efforts to make the space more available for community needs don't overshadow the primary call to steward the congregation's spiritual life.

Community Partnerships

Developing strong community partnerships is a crucial opportunity for churches looking to maximize the impact of their properties. By opening their facilities to local organizations and community groups, churches can foster stronger ties within the neighborhood and enhance their ability to serve. These partnerships can generate additional revenue through space rentals, collaborative programs, or funding opportunities for innovative projects that benefit the entire community.

However, churches should carefully consider who they partner with and how these partnerships align with their values and theology of stewardship. Some churches may avoid collaborations with for-profit entities, while others might see such partnerships as a creative way to further their mission.

Regardless of the approach, if a church considers opening its space to its neighbors, it is essential to involve community stakeholders in shaping how the space will be used. Including community partners in the planning process not only ensures that the space is utilized in the most beneficial ways but also fosters a stronger investment in the space and its activities. This approach creates greater community buy-in, helping the church maintain its role as a vital and enduring presence in the neighborhood.

Preservation and Modernization

Balancing the need to preserve historic church buildings with the necessity of modernization is a challenge that presents significant opportunities for churches. Many church leaders are deeply concerned with how their properties can continue to serve future generations while maintaining their historical and architectural integrity.

"We're fixing that tower so that the next generation doesn't have to worry about it and can focus on something else,” Pastor Larry Kim of Central Square Church in Cambridge, Massachusetts, said. “Our job is to ensure that this remains a church, a place of worship for the next generation, and that it continues. When I watch our kids run around, have space to play, grow, and be discipled, I feel like it’s really been worth it—worth paying for the restoration of that window that gives sunlight to my kids as they’re being discipled."9

Pastor Lange from East Coast International Church in Lynn, Massachusetts, said he is passionate about leaving a legacy.

“All of our facility, building, and capital campaigns are called ‘Legacy,’” he said. “We're driving home this idea that all of this is for the next generation and the generations beyond that.”

Investing in energy-efficient upgrades, accessibility improvements, code compliance, and sustainable practices can reduce long-term costs and align with a church’s commitment to environmental stewardship. These updates can also make the space more welcoming and functional for a broader range of activities and community uses.

“We’re fixing that tower so that the next generation doesn’t have to worry about it and can focus on something else. Our job is to ensure that this remains a church, a place of worship for the next generation, and that it continues.”

However, securing grants and funding for preservation projects can be challenging. Churches need to seek resources that support the physical upkeep of the building while allowing them at the same time to invest in the community and the people who use the space.

Working with experts in historic preservation and exploring innovative funding options—such as community crowdfunding or matching grants—can help congregations navigate this complex landscape. If a church does not already have a historic designation, exploring that option could unlock access to a pool of funding that would otherwise be unavailable.

It's critical to recognize the significant challenges involved in preserving historic spaces. There’s often a lot of red tape, and the specialized skills required for restoration are typically offered by only a few companies, meaning that the millions of dollars spent usually leave the local community.

To address these issues, it's essential to create accessible training and education as well as opportunities for emerging small businesses to build the capital needed to offer these services, thereby fostering greater equity within the preservation system.

Churches should also establish budgets for ongoing maintenance, preventative work, and future renovations, and develop plans for funding these needs.

The Church’s Stewardship Moment

As churches in Boston and beyond navigate the complexities of property management, there’s a unique opportunity for congregations to take the time to reflect on their approach to utilizing their space. The theology of a church’s decision-makers plays a crucial role in the stewardship of resources and assets. Aligning a congregation’s property with its mission—and finding sustainable ways to do so—is paramount.

While some congregations or denominations may have leaned toward protecting their assets for various reasons, this article presents a challenge to be more generous with the resources God has blessed them with for the benefit of the wider community and to consider how their buildings can be used not just as places of worship, but as dynamic resources that contribute to the shalom of the city. The decisions churches make today about stewarding these spaces will shape their legacies for generations to come.

“Be creative and take risks,” said Mr. Jarell from the Cathedral Church of St. Paul in downtown Boston. “I think that churches, in general, are at an interesting crossroads right now, where the traditional use of church space has diminished—we all know that. But there's an opportunity right now for churches to articulate a vision for how space can be used in a different and innovative way.”

“Be creative and take risks.”

Churches can begin that journey by asking themselves how they can leverage their assets, what causes they can support, and how they can galvanize their local neighborhoods.

“Can we inspire passion among everyone in our community—not just people that attend church on Sundays or have been parishioners for years and years, but also people that may have never thought to enter the doors of a church before?” Mr. Jarell said.

As he considered the Cathedral’s role in the life of the city over the past few years, Mr. Jarell reflected on how much has changed downtown since the coronavirus pandemic. There was little conception of what life would be like. But the aftermath presents new possibilities.

“Through this process of everything crumbling and falling apart, and things changing, and the world morphing into something new, we have an opportunity to reshape what the life of our city looks like,” he said. “These sacred spaces in time are liminal moments, and we're in one right now. The opportunity is there, so seize it.”

- Mathew Jarell, interviewed by author, September 29, 2023.↩︎

- Kurt Lange, interviewed by author, November 3, 2023.↩︎

- Partners for Sacred Places, “The Economic Halo Effect of Historic Sacred Places,” Sacred Places: The Magazine of Partners for Sacred Places, The National Report, 2016, https://sacredplaces.org/info/publications/halo-studies/, accessed October 3, 2024.↩︎

- Davie Hernandez, interviewed by author, August 29, 2023.↩︎

- Daniel Chan, interviewed by author, September 20, 2023.↩︎

- Marc Levefre, interviewed by author, November 10, 2023.↩︎

- Partners for Sacred Places, “The Economic Halo Effect of Historic Sacred Places,” 5.↩︎

- Yulieth Ramos, interviewed by author, August 30, 2023.↩︎

- Larry Kim, interviewed by author, October 11, 2023.↩︎

Four Ways Churches Use Their Space for Economic Empowerment

Some churches have successfully transformed their properties into dynamic community centers offering various services, from food pantries and after-school programs to cultural events and neighborhood meetings.

Four Ways Churches Use Their Space for Economic Empowerment

by Saranya Sathananthan, Researcher in Residence

In light of the city's needs, there are unique opportunities for churches to partner with civic leaders, developers, nonprofits, and other stakeholders to further Boston's economic empowerment and vitality. Churches can leverage the underutilized spaces in their buildings for use as commercial kitchens, early childhood education such as daycare centers and schools, affordable housing, and spaces for the arts.

Beyond the economic impact, churches also have the potential to serve as vibrant community hubs and cultural centers, addressing a wide range of local needs. This opportunity allows churches to expand their role beyond spiritual nourishment to include social, educational, and cultural engagement. Some churches have successfully transformed their properties into dynamic community centers offering various services, from food pantries and after-school programs to cultural events and neighborhood meetings.

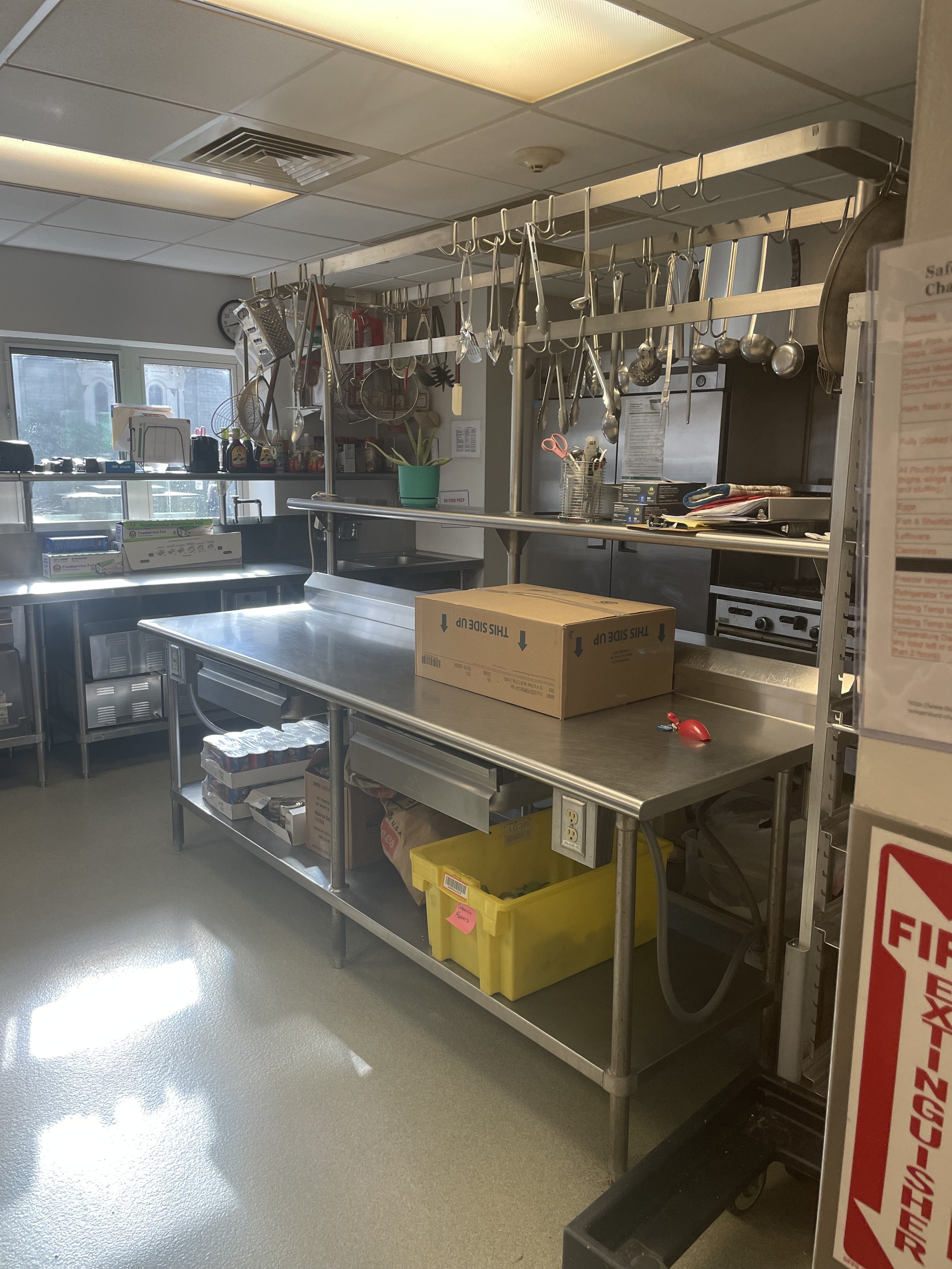

1. Commercial Kitchens

Many churches have large kitchens with various appliances and accessories that remain underutilized for most of the week. Occasionally, congregation members use these spaces to prepare food for church events or partner with nonprofits to cook meals for distribution or soup kitchens. However, many of these kitchens are not licensed, limiting their use. Imagine the significant economic impact of investing in transforming these kitchens into licensed commercial kitchens.

Food served at public events must be prepared by businesses operating out of licensed kitchens, with the appropriate permits for food handling. Boston has a limited number of shared commercial kitchens where caterers can legally cook for events. Churches offering these spaces to community members would provide crucial support to small businesses needing such facilities throughout the city.

However, running a licensed shared kitchen involves navigating considerable regulatory red tape. Therefore, churches would need to partner with individuals or businesses experienced in this area and develop a partnership where the business operates out of the church space. This collaboration could unlock new opportunities for both the church and the community, contributing to local economic growth.

Fig. 1 A commissary kitchen operating out of First Baptist Church Jamaica Plain.

Fig. 2 A commissary kitchen operating out of First Baptist Church Jamaica Plain.

2. Early Childhood Education (Daycares and Schools)

The cost of childcare in major cities like Boston is staggering. The average weekly daycare cost in 2023 was $321, up 13% from $284 in 2022, which can amount to over $1,500 per month1—if you're fortunate enough to find it that low here in the city. Families often have to tap into savings and rely on both household incomes to cover these expenses. Parents face difficult decisions about whether it's even worth it for both to return to work, as much of their income goes directly to childcare costs.2 The issue is compounded by the limited supply of childcare options, leading to lengthy waitlists, sometimes extending for a year before the child is even born.

In the United Kingdom, many churches have stepped in to provide childcare services, offering much-needed support to families.3 For churches in Boston, creating affordable daycare or a private preschool could be a meaningful social enterprise, especially if there are individuals within the congregation who have the knowledge and passion for running such an initiative. Alternatively, churches might consider partnering with individuals or organizations interested in starting their own school or daycare, provided they share similar values—even if the focus is not on Christian education.

There are, of course, regulatory restrictions to consider, such as compliance with building codes. However, by working closely with a school or daycare partner, churches can either collaborate to make the necessary changes or include those requirements as part of the agreement, ensuring that the partner is responsible for compliance. While some churches may have dedicated spaces for a school or daycare, utilizing shared or multi-use spaces is becoming more common—especially in urban settings. What works best will depend on the needs of both the church and the childcare provider, and it will likely require some compromise to find a solution that benefits everyone involved.

Fig. 3 Entryway to a sanctuary that is used as a preschool during the day at First Baptist Church of Jamaica Plain.

Fig. 4 Entryway to a sanctuary that is used as a preschool during the day at First Baptist Church of Jamaica Plain.

3. Affordable Housing

The 2023 Greater Boston Housing Report Card, produced by the Boston Foundation, highlights a growing crisis. An increasing number of residents across all income and education levels are leaving the region due to skyrocketing housing costs for rentals and homeownership. The existing housing supply does not meet the demand. And Massachusetts lags behind other states in producing more housing—particularly housing that is affordable to middle- and low-income individuals and families.

The Metro Mayors Coalition, which comprises 15 municipalities in Massachusetts, has set a goal to produce 185,000 new housing units between 2015 and 2030 to address this imbalance. However, Boston remains one of the most expensive rental markets in the nation, and the disparities across racial lines are significant according to the housing report card: “Black and Latino families are still far less likely than White or Asian families to own homes in Greater Boston.”4 The report also examined affordability, defining a household as "cost burdened" if it spends more than 30% of its income on housing. The findings were stark: “The majority of renter households in Greater Boston earning less than $75,000 are cost burdened. Overall, about half of renters and a quarter of homeowners in the region are cost burdened.”5

Imagine if churches could help address this issue by creating affordable housing for renters and homeowners in Boston, particularly for those most vulnerable to being financially pushed out of the city. The income saved by residents through church-created affordable housing could significantly contribute to the city’s economic vitality in numerous other ways. For churches open to exploring this non-traditional option, partnering with developers to create affordable housing on their properties is a viable path. Some churches in Greater Boston, such as East Coast International Church in Lynn, Massachusetts, and St. Katharine Drexel Parish in Roxbury, Massachusetts, are already doing this. While it's not easy—requiring access to various city, state, and federal incentives and working with mission-oriented developers rather than purely profit-driven ones—it can make a substantial impact.

For churches where working with developers and funding agencies feels too complex or misaligned with their values, there are other ways to provide affordable housing. Several churches in Boston still own other properties, such as parish houses, which were traditionally used to offer free or low-cost housing for clergy and their families. Many are considering using these parish houses or other properties to provide housing for vulnerable groups. For instance, Restoration City Church in Roxbury, Massachusetts, operates Jasmine’s House, which offers a haven for women rebuilding their lives after being trafficked. Other churches use parish houses as temporary housing for migrants and refugees. There are numerous possibilities.

Moreover, many parachurch ministries actively seek housing for the different groups they serve. This situation presents an excellent partnership opportunity for churches to make their housing assets available for ministry purposes, further extending their impact on the community.

4. Spaces for the Arts

Many major cities are committed to funding the arts. In Boston, significant investments have been made to ensure an equitable recovery for the arts and culture sector following the coronavirus pandemic, supporting everything from theater and dance to public art and libraries. In fiscal year 2023, the City of Boston allocated $25 million in American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) funding to bolster arts and cultural activities in downtown Boston and neighborhoods across the city as part of their community revitalization efforts. While ARPA funding has concluded, opportunities for the arts continue to thrive.6

Imagine artists using church spaces as studios, galleries, rehearsal spaces, and performance venues. Church communities sometimes undervalue artists, yet they contribute immensely to the cultural vitality of our neighborhoods.

See "Christian Creatives and the Church"

There are numerous opportunities for churches to collaborate with local artists and even co-apply for funding to support public art initiatives. By utilizing non-traditional spaces, such as church properties, for artistic endeavors, churches can create vibrant cultural hubs that benefit and positively impact the community.

Fig. 5 Performance of Benjamin Brittain's "The Prodigal Son" by Enigma Chamber Opera in February 2024 in the Cathedral Church of St. Paul’s sanctuary in Boston. According to the church, part of its strategic plan is to “strengthen the civic fabric by hosting events at the intersection of arts, education, and faith that bring together a wide range of people and address relevant issues of our time.” Photo credit: Rev. Amy McCreath

Fig. 6 The future location of The Center for Faith, Art, and Justice at First Baptist Church of Jamaica Plain in Boston. This space was destroyed by a fire in 2005, and efforts are underway to fundraise to complete its restoration.

Fig. 7 The renovated sanctuary will feature a gallery space. Rendered images courtesy of First Baptist Church of Jamaica Plain.

Fig. 8 The renovated sanctuary will feature a gallery space. Rendered images courtesy of First Baptist Church of Jamaica Plain.

By leveraging their properties in these strategic ways, churches can play a vital role in the economic vitality of their neighborhoods. When cities invest in church spaces, it creates a win-win situation, enabling churches to continue their presence and contributions to the community.

These are only a few opportunities I see having potential for impact. But it’s important to note that the first step before launching into any of these paths is for church leaders to begin these conversations with community stakeholders and city leaders to discern where there is momentum for collaboration and building something new together. It may take years before anything visible is accomplished, yet those relationships built from the onset are foundational for long-term success.

- Care.com Editorial Staff, “This is What Child Care Costs in 2024,” 2024 Cost of Care Report, CARE, Jan. 17, 2024, https://www.care.com/c/how-much-does-child-care-cost/.↩︎

- Kristi Palma, “Child Care Expenses are Crippling, Say Boston.com Readers,” Boston.com, March 2, 2023, https://www.boston.com/community/readers-say/child-care-expenses-are-crippling-say-boston-com-readers/.↩︎

- Hope Together, “Talking Toddlers,” (Research Report), 2020, accessed October 3, 2024, https://www.hopetogether.org.uk/Publisher/File.aspx?ID=257900.↩︎

- Sonia Gupta and Sandy Kendall, eds., “The Greater Boston Housing Report Card 2023 with a Special Analysis of Community Land Trusts,” The Boston Foundation, 2023, 32, accessed October 3, 2024, https://www.tbf.org/news-and-insights/reports/2023/november/2023-greater-boston-housing-report-card.↩︎

- Gupta and Kendall, “The Greater Boston Housing Report Card 2023,” 40, https://www.tbf.org/news-and-insights/reports/2023/november/2023-greater-boston-housing-report-card.↩︎

- “Strengthening Arts and Culture,” City of Boston: Mayor’s Office of Arts and Culture. July 1, 2022, https://www.boston.gov/departments/budget/strengthening-arts-and-culture.↩︎

What happens when church buildings close?

Churches faced with aging buildings, lack of parking, and aging, dispersed membership may find selling their buildings necessary—or even advantageous. What happens to the buildings when they do?

Trends and status of Christian institutional property ownership in the City of Boston

by Rudy Mitchell, Senior Researcher

Boston is home to about 575 Christian churches. While many of these rent space from other churches, organizations, or private owners, a significant number of congregations own and meet in traditional church buildings, former commercial properties, or converted residential buildings.

Currently, churches and their denominations own about 320 properties in Boston, including 256 buildings primarily used for worship, ministry, and service.

In recent decades, some church-owned buildings have been sold to other congregations, developers, and private business owners. As a result, about 45 buildings formerly owned by churches or religious organizations have been lost to the Christian community as well as the communities and neighborhoods these churches once served and called home.

These churches not only contributed to the spiritual well-being of their neighborhoods but also played an important role in sustaining the social fabric of their communities. Many provided a variety of social services and enriched civic life. Memories of important life events were tied to these sacred spaces.

As a result, the loss of these congregations and sacred spaces has had a deeper impact than is often realized.

In a constantly changing city and culture, there are many reasons why congregations decline, and church buildings are sold. To stay vital to the life of the community, churches require spiritual renewal and the ability to adapt to younger generations. Shifting demographics also can affect congregations, particularly when their members move to different areas farther from the church building.

In the Boston area, this movement of people is influenced by ever-rising housing costs and, in some neighborhoods, gentrification: the process of higher-earning and more educated residents moving into historically marginalized neighborhoods. While gentrification brings increased financial investment and renovation to a neighborhood, it often also leads to a rise in housing costs, which results in the displacement of long-time residents. This dynamic disrupts congregations, as church members may be displaced or move elsewhere. Churches faced with aging buildings, lack of parking, and aging, dispersed membership may find selling their buildings necessary—or even advantageous. Sometimes, congregations that were renting space are no longer able to afford the cost.

What happened to these buildings?

Congregations, which own and meet in residential houses, often adapted the first-floor space for worship. In several cases, when sold, the new owner has changed the occupancy, converting the space into a residence and adding an additional unit.

Iglesia de Dios Pentecostal at 68 Day St. in Jamaica Plain used the first floor for church services, but after the building was sold, the first floor was changed into a residential unit.

The Greater Community Baptist Church at 27 Howland St. in Roxbury used to meet in a converted house with a brick addition on the front. When this property was sold, the new owner removed the addition and converted the building to a two-family house.

Iglesia de Dios de la Profecia owned a tax-exempt converted house at 20 Moreland St. in Roxbury, which was sold and converted into a private two-family residence.

On Melville Avenue in Dorchester, the Salvation Army used a large house and 35,000-square-foot lot as a ministry center and church called Jubilee Christian Fellowship. When sold in 2022, the property was turned into a two-family luxury residential building.

While several houses used as church buildings have been sold, congregations such as the Church of God and Saints of Christ on Crawford Street and Spirit and Life Bible Church on Columbia Road continue to meet in converted houses.

In the past, numerous churches met in commercial or storefront properties, even in neighborhoods like the city's South End. Some storefront churches rented space, while others purchased the buildings when prices were relatively low. As rental prices rose and neighborhoods gentrified, several churches renting storefronts had to move out or close.

One rental storefront church space became a dental office, and another became a restaurant. Several church spaces have become laundromats. For example, the Full Life Gospel Center in Codman Square decided to sell its storefront property and buy another Dorchester church building whose Haitian congregation had moved to a former synagogue in Randolph. The former Full Life Gospel Center property on Washington Street was then renovated into a laundromat.

“Over the last 50 years in Boston, as the city has changed and property has become much more expensive, many former storefront churches have disappeared.”

Although churches, which own commercial-type space, generally have not needed to move, some have chosen to sell and relocate or buy other buildings. Grace Church of All Nations in Dorchester chose to sell its storefront property to a CVS Pharmacy and purchased a former Christian Science Church in Roxbury. Over the last 50 years in Boston, as the city has changed and property has become increasingly expensive, many former storefront churches have disappeared.

From the 1950s to 1970s, as neighborhood churches in Boston declined and congregations were leaving the city, many church buildings and synagogues were sold or passed on to new Black, Haitian, or Hispanic congregations. In recent years, some church buildings have been sold to other congregations, while many others have been lost to the religious community altogether.

Some churches with valuable properties may have concluded their assets could be better spent on more extensive, less expensive, and more modern facilities in other areas, closer to where their congregants live. Those congregants who used to live in Lower Roxbury, Roxbury, or Dorchester may now live outside the city because of escalating housing costs in Boston. Although some churches that have sold city buildings have rented temporarily, most have purchased other buildings.

The 45 church buildings cited earlier represent over 30 congregations that have closed permanently. Others have either moved elsewhere in the city—such as Grace Church of All Nations, New Hope Baptist Church, Full Life Gospel Center, Mount Calvary Baptist Church, Church of God of Prophecy, Boston Chinese Evangelical Church—or moved out of the city—such as Trinity Latvian, Christ the Rock Metro, Concord Baptist Church, and Ebenezer Baptist. Some congregations, such as Holy Mount Zion Church, New Fellowship Baptist/Spirit and Truth, and Mount Calvary Holy Church, are left in limbo due to fires, structural deterioration, or financial constraints.

Although some churches have relocated outside the city of Boston, the overall number is still relatively small compared to the total number of churches currently in the city. As lower- and middle-income Boston residents, as well as new immigrants, settle in communities farther from downtown, new churches are also starting up in these communities. At the same time, inner-city churches are losing members who no longer commute back to their former congregations.

When traditional church properties are sold to non-church buyers, they are mostly converted into market-rate residential units, such as condos or apartments. However, there are notable exceptions to this: St. James African Orthodox Church in Roxbury, Hill Memorial Baptist Church in Allston-Brighton, and Boston Chinese Evangelical Church in Chinatown.

St. James African Orthodox was rescued from demolition and private development through neighborhood activism and the help of Historic Boston, Inc., which purchased the building, made repairs, and eventually resold it to a community organization, the Roxbury Action Program. (In the process, Historic Boston, Inc. tried to interest other churches and community organizations in developing the building cooperatively; however, no churches could take on the project.)

Hill Memorial Baptist worked with a neighborhood development organization and the City of Boston to see their church sale result in plans for affordable senior housing, with the church building preserved to serve as a social center for the new residents. The church, its denomination, and the Allston Brighton Community Development Corporation went through a five-year partnership and planning process to achieve positive outcomes for the community and church.

Boston Chinese Evangelical is another unique example of a traditional church-building sale. Over the years, church leaders were in dialogue with the City of Boston and the Boston Public Schools about their church building and property in Chinatown, which was in a strategic location next to the Quincy Elementary School. After the congregation purchased a large, nearby building at 120 Shawmut Ave., it sold its church building to the city. The church building was demolished, and the new Josiah Quincy Upper School was built on the site.

While the St. James African Orthodox and Hill Memorial Baptist congregations closed, the Boston Chinese Evangelical congregation continues to use a diverse portfolio of property that includes rented worship space at the Josiah Quincy Elementary School, its multi-purpose building at 120 Shawmut Ave., and a Newton, Massachusetts, satellite church building.

Preserving and sustaining church congregations and their properties is critical for the health of Boston’s neighborhoods. Churches’ physical and spiritual presence contributes to their communities on many levels.

Congregations that want to stay in their current neighborhoods can seek ways to serve others and sustain themselves by renting space to community groups or other congregations. Churches looking to close or relocate and sell can plan and consider positive outcomes for their building by selling to another church or community-serving organization. They can also work to see community development efforts, such as community centers or affordable housing units, built within the church or on its site.

Shared Worship Space - An Urban Challenge and a Kingdom Opportunity

With limited meeting space in some of our cities, how do churches who practice their faith in different ways gather under the same roof and learn to love each other?

Resources for the urban pastor and community leader published by Emmanuel Gospel Center, Boston

Emmanuel Research Review reprint

Issue No. 74 — January 2012

Introduced by Brian Corcoran, Managing Editor, Emmanuel Research Review

One body, one building? Being neighbors is one thing, but when churches gather under the same roof, much deeper and intricate conditions emerge that remind us of the character, nature, calling and Kingdom purpose of the Church in a diverse urban environment. Dr. Bianca Duemling, Assistant Director of EGC’s Intercultural Ministries, outlines the challenges and opportunities that present themselves when multiple congregations consider sharing the buildings they use for worship.Employing a biblical, intercultural, and practical perspective, Bianca, along with local leaders and her research colleagues, “hope that this article enhances the understanding of the dynamics and challenges of sharing worship space and helps congregations to develop healthy and supportive relationships with each other to manifest the unity of the body of Christ across ethnic lines.”

Shared Worship Space - An Urban Challenge and a Kingdom Opportunity

by Bianca Duemling, with the research assistance of Cynthia Elias and Grace Han

Contents

Factors Contributing to the Need of Shared Worship Space - an Introduction

Biblical Perspectives on Sharing Worship Space

Cultural Differences and Power Imbalance

Aspects of Sharing Worship Space

Advice from Sharing Worship Space - Experts

Conclusion: Sharing Worship Space - a Long-Term Solution?

Resources

Section One: Factors Contributing to the Need of Shared Worship Space - an Introduction

Sharing worship space is a reality in the urban context as space is very expensive and limited in availability. During the “white flight” in the 1960s, many congregations moved to the suburbs. Consequently, the number of majority-culture1 churches in many North American cities declined. At the same time the “Quiet Revival”2 unfolded and spiritual vitality flourished among immigrants in Boston. On every corner, new immigrant congregations emerged, often as house churches or in former storefront shops. Additionally, there is a new wave of young church planters who intentionally moved into the city to plant churches.3

As congregations grow and need more space, they look for alternatives. Some rent space in office buildings, hotels or schools4, but most of them reach out to congregations owning buildings to share space. Lack of space and lack of financial means makes it very difficult to find appropriate worship space in the city.

Facts about sharing space in Boston, Cambridge, and Brookline:5

32% of all congregations share worship space, in total 214 congregations

73.6 % of these congregations share with one other congregation

16.1% of these congregations share with two other congregations

10.3% of these congregations share with four or more congregation

82.8% of these congregations share with congregations of a different denomination

17.2% of these congregations with congregations of the same denomination

95% of these congregations share with congregation other than their own ethnic background.

Different Shared Worship Space Arrangements

The most common way of sharing worship space is having two or more independent congregations under one roof. One of them owns of the building and others are invited in. This article will mainly focus on their situation. However, there are other ways to share worship space. One example is the multi-congregational model. Different language groups are gathered under a joint leadership and board of elders. This includes a joint ownership of the building. Grace Fellowship in Nashua is such an example. Two of the Associate Pastors are also pastors of the Brazilian Church and the Russian/Ukrainian Church.6 Another rare arrangement is a joint ownership, when independent congregations build or buy a church building together.Background and Structure of this Article

After Intercultural Ministries at EGC had been approached for advice on this matter several times, we started this research project to learn from the experience of different congregations about sharing worship space. Moreover, we found out that little has been written about sharing worship space well; even denominations have not addressed that issue or developed guidelines for their member congregations.7 In this article, I draw from inspiring conversations with many pastors.8 I thank all of them taking the time to honestly share their story and struggles with me!The proximity of diverse congregations when sharing worship space offers a great potential to connect with each other across ethnic lines and witness the beauty of unity in diversity to the neighborhood. The reality, however, shows that sharing worship space is very challenging. It often causes much frustration for the congregations involved.

I hope that this article enhances the understanding of the dynamics and challenges of sharing worship space and helps congregations to develop healthy and supportive relationships with each other to manifest the unity of the body of Christ across ethnic lines. Making shared worship space work needs investment and commitment; there is no magic bullet to solve the challenges, and every situation differs from another.

First, I will unfold the reasons and importance for sharing worship space from a biblical perspective. Second, I will address cultural differences and how the power imbalance in our society impacts sharing worship space. After that, I will talk about how to share worship space and which different aspects need to be factored in. Also included will be advice from those I interviewed for those intending to share worship space. Moreover, in the appendix you will find some resources on sharing worship space.

Section Two: A Biblical Perspective on Sharing Worship Space

The Bible gives us many examples why sharing worship space is essential for the Body of Christ and closely connected with who Jesus wants his disciples and his Church to be. In this section I want to briefly address five biblical aspects9 to consider in this context which are interconnected. Some of the aspects might refer more to the situation of the owner of the church buildings, whereas others are important for both parties.

The Body of Christ – a Loving Relationship

The two most meaningful passages in this context are the image of the Body of Christ and the new commandment.

In 1 Corinthians 12, Paul describes the church as one interconnected Body of Christ. In verses 24-26, he especially mentions the nature of the relationship: “But God has put the body together, giving greater honor to the parts that lacked it, so that there should be no division in the body, but that parts should have equally concern for each other. If one part suffers, every part suffers with it; if one part is honored, every part rejoices with it.”

In line with this image is Jesus’ new commandment to love one another (John 13:34-35). Love is always more than words. Love implies consequences as described in 1 Corinthians 13. Love also means to humbly serve one another, as stated in Galatians 5:13.

Moreover, sharing housing, food, and economic resources is characteristic of the early Church, as described in Acts 4. The reference is often made to become like them again. Sharing worship space is a great opportunity to pick up the characteristics of the early church and set them into practice. Through that the unity in diversity of the Body of Christ is manifested.

Missional Impact

Another aspect is the missional impact of unity. Jesus emphasized in John 17:21 shortly before he died: “that all of them may be one, Father, just as you are in me and I am in you. May they also be in us so that the world may believe that you have sent me.” There is a close connection between being one and the aspect that the “world may believe.” In my understanding, this verse states very clearly that unity is a key to renewal and revival. Moreover, sharing worship space, especially across ethnic lines, is a witness to the community that Jesus is relevant today. He bridges the gap of segregation and brings peace and reconciliation.

Opportunity of Spiritual Growth

Sharing worship space might not increase a church’s growth numerically, but surely can enhance spiritual growth and maturity. It is very easy to talk about a Christlike life from one's own comfort zone. But sharing worship space and stepping out of the comfort zone gives the opportunity to set the Gospel in practice. It shows how seriously a congregation lives the fruits of the spirit as mentioned in Galatians 5:22-23. Hence, sharing worship space is an opportunity of manifesting a deeper kind of unity that surpasses the state of being kind to each other.

The interaction with Christians from all over the world challenges the cultural elements of our Christian practices and leads the focus on the essential Christian faith. Mutual mentoring and encouragement as well as learning from each other's strength help us to mature in Christ. It is an excellent practice to embrace our poverty.10

Additionally, understanding of the global Kingdom of God increases, as well as affection for other parts of the world, through the immigrant group sharing space. Thus, leaders and members can develop intercultural competency, which is a much needed skill in our diversifying society.

Good Stewardship

In the parable of the talents, God has entrusted men with bags of gold to use wisely for the Kingdom of God (Matthew 25:14-30). In 1 Peter 4:10 it is even more explicitly expressed that “each of you should use whatever gift you have received to serve others, as faithful stewards of God’s grace in its various forms.” A church building, for example, can be seen as such a bag of gold that should be used wisely for the sake of people’s life and the building of the Kingdom of God.

Growing the Kingdom of God

One of the great challenges of the Body of Christ is to develop a Kingdom perspective beyond the walls of a congregation’s own activities. In assisting church planting through sharing worship space or incorporating an immigrant congregation as a part of one's own mission, we are involved in advancing the Kingdom of God.

Church planting and the growth of a congregation is something that God is doing by using us. Nurturing vitality through sharing space means aligning with God’s plan.

These Scripture passages and many more indicate that sharing worship space is not just a business deal between two independent parties, but also an undertaking within the one Body of Christ. The source of consideration should be the advancement of the Kingdom of God. If growth occurs because a congregation has opened their space for a church plant, it is as important as if the same congregation would add new believers to their flock. In either case it is for the advancement of the Kingdom of God and the Glory to God.

Congregations need to shift their mental models. If one congregation is not able to send out church planters, they can still be involved in church planting by sharing worship space. It needs to be understood that helping other congregations fulfill their calling is a valid Kingdom mission and ministry.

New mental models generate different questions. It is not to ask: “How do I (or does my congregation) get the job done?”, but: “How does the job get done?” — no matter how God uses me and my congregation.11