BLOG: APPLIED RESEARCH OF EMMANUEL GOSPEL CENTER

Not That Kind of Racism

Well-meaning people can act in ways that have racist impacts they wouldn't want. Don't be one of these people! Learn all you can to avoid being an accidental racist through this heartfelt reflection.

Not That Kind of Racism

How Good People Can Be Racist Without Awareness or Intent

By Megan Lietz

Megan Lietz, MDiv, STM, directs Racism Education for White Evangelicals (ReWe), a program of EGC’s Race & Christian Community Initiative. The intended audience of ReWe ministry and writing is White Evangelicals (find out why).

In the tragedies of Charlottesville, VA, as a White person, it’s easy for me to see such hate and think, “How awful! That’s racist. Thank God I’m not a racist like that.” In doing so, I affirm my sense of being a good moral person and find comfort in the fact that I’m not like those I’m condemning.

In reality, White people cannot separate ourselves from the problem of racism. Even if we consciously reject racism, the biases and behaviors that contribute to and sustain injustice crop up in our actions. Racism persists not because of the hate of a few White supremacists, but because well-intentioned White people regularly contribute to racial inequity in ways that we may not be aware of or intend.

Expanding our View of Racism

Institutional and structural Racism

While interpersonal racism between people is still common, racism occurs as much if not more at the organizational and systemic level, which can be more difficult for White people to recognize.

For example, people with Black-sounding names are 50% less likely to get called for an interview compared to people with White-sounding names. This bias is one of many contributors to vast disparities between the median net worth of White people as compared with Black people or Hispanic people.

Implicit Bias

How we see and respond to situations is shaped by unconscious personal biases and stereotypes. We all have them, and they don’t necessarily align with our explicit beliefs. These can come out in casual interactions that can make people of color feel disrespected or devalued. They can also have a broader impact when shaping the decisions of policymakers, the prescriptions of doctors, or the actions of law enforcement agents.

To perpetuate racism, people don’t have to be ill-intentioned, or even aware they are contributing to injustice. By not actively resisting racist dynamics—and sometimes even by attempting to do so without proper understanding—we can contribute to a system that sustains inequality and racism.

Reflecting On Our Experiences

White people need education and reflection to see how we may be participating in injustice. We must look inward with openness, intentionality, and humility.

I’ve uncovered racism in my own life—how I’ve participated in it, benefited from it, and perpetuated it—which I share below. May my examples inspire your reflection, awareness, and action.

MY INSTITUTIONAL RACISM

Institutional racism is discriminatory rules, policies, and practices within organizations or institutions.

I’ve supported businesses known to treat people of color in unfair ways because using their services was convenient for me.

I’ve encouraged ways of thinking and doing that reflect my culture. For example, I feel that a meeting has gone well if we’ve followed my linear-thinking agenda, avoided conflict, and produced certain kinds of outputs. I tend to devalue people who don’t excel in the skill sets I value and prefer to work with people who think and act like me. If the leadership of my organization shares my lens on what “being effective” or having a good meeting looks like, I’ll thrive while people from other cultural experiences, who may have their own methods and practices for effectiveness that are just as valid, will be at a disadvantage.

My Structural Racism

Structural racism is persistent racial injustice worked into and maintained by society.

Media and historical narratives that paint White people as dominant leaders and valuable assets have shaped my self-perception. I have assumed my presence and leadership is desired even in spaces where racially I am in the numerical minority. I’ve had to learn to be intentional about taking a support role.

Because, historically, people of my skin color have had economic opportunities unavailable to people of color, my family and I had the financial resources to buy a home—one in a predominantly Black neighborhood. While we moved with the intent to learn from and invest in our community, we also contributed to gentrification and its associated displacement.

My Implicit Biases

Implicit biases are unconscious personal biases and stereotypes.

White ideologies have shaped in me a pro-White view of how the world works. I grew up with the belief that people can succeed if they try. As a result, when I interact with people of color who are struggling, my initial reaction may be that they need to work harder, must be doing something wrong, or don’t have what it takes, rather than considering the impact of systemic racism.

After hearing a Black man talking about the ways he loves and cares well for his daughter, I found myself being especially encouraged. Upon further reflection, I realized that I wouldn’t have had the same response to a White man because I would’ve expected him to be a good father. Sadly, my encouragement came from an expectation that men of color are less likely to be involved fathers.

I spoke Spanish to a woman who appeared to be Hispanic/Latino, assuming it was her first language. Though this was my attempt to value her culture, she could’ve perceived it as reflecting a belief that people from her ethnic group don’t speak English, or must speak Spanish.

A Call to Self-Reflection

In acknowledging ways we’ve been perpetuating racism, we need not label ourselves as bad people. We need not declare we are “a racist,” in the sense that we often use that label—as a damning marker of our identity.

But we must admit that we can, and often do, perpetuate racism. We can have a racist impact, even without intent or awareness.

Acknowledging our potential for racist impacts is the first step in changing our thoughts and behavior. We can lead in our spheres of influence by first changing ourselves.

Exploring our racist tendencies isn’t an easy journey. But we can make real progress, one step at a time, empowered by God’s grace. I invite you to join me in self-reflection.

Reflection Questions

How do any of my life’s examples of institutional or structural racism resonate with your experiences?

As you discover any unjust attitudes or behaviors, how might you want to connect with God about it—in expressing lament or confession, in seeking wisdom, forgiveness, courage, or hope? What does the Gospel mean for you in this moment?

Do you notice attitudes or behaviors in your workplace, church, or other groups you participate in that contribute to racial disparity and division? With whom could you share your concerns?

Take Action

Stopping Racism Starts Here: 5-Minute Entry Points

Racism in Boston is a big problem. But the road to racial harmony starts with a single step. Check out these recommended videos and special features, each of which take under five minutes to explore.

Stopping Racism Starts Here

Five-Minute Entry Points

by Megan Lietz, EGC Race & Christian Community Initiative

Busy? We get that. Troubled by racism? Good. Here are five resources you can explore in under five minutes about racism in America today.

The current face of racism

Some forms of racism—the legalized segregation in Jim Crow laws, for example—are thankfully behind us. But other forms of systemic racism—such as the mass incarceration of Black men—still create inequitable experiences for people of color to this day.

The Racism is Real video by Brave New Films explores some everyday ways racism creates different experiences for White and Black people today.

How RacisT History Impacts Today

Do you live in a pretty homogeneous neighborhood? Most people in the US do. While we may like to think that where we call home is shaped by our personal preferences or “just the way things are," the racially segregated neighborhoods we live in today are the product of our history.

Play around on PBS’ Race: The Power of Illusion website to learn how housing policies in the 20th century have had a profound impact on today’s neighborhoods and the resources that are available to them.

Implicit Bias

No one likes to think they’re biased. The six brief Who, Me? Biased? videos from the New York Times explore how we have all been unconsciously shaped to have biases. When we recognize this, we can see that even good, well-intentioned people can contribute to inequality. We’re all part of the problem.

The good news is that, with education and exposure, we can all take steps to be less biased. We can take intentional action towards equality.

Color-Blind

One thing that I often hear among White people is that they are “color-blind.” This is intended as a positive comment, implying that they don’t treat people differently based on the color of their skin. While well-intentioned, this lens can be counterproductive. This article by Jon Greenberg explains why.

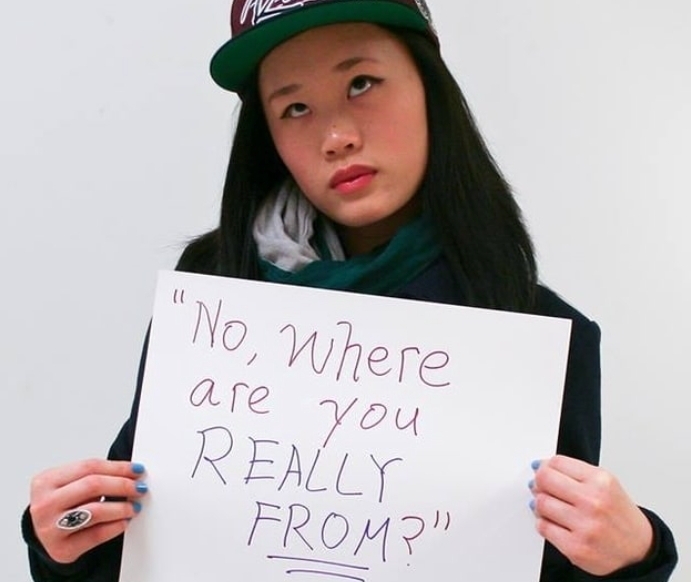

Microaggressions

Microaggressions are day-to-day things we may say or do that can hurt people of color, sometimes without our intending or realizing it. Check out this Buzzfeed photo journal for some examples of microaggressions.

To explore a broader list of microaggressions, what they can subtly communicate, and why they are problematic, check out this chart:

What do you think is the next step in dismantling racism?

Reflections on Charlottesville

As a community of Christians who are grieved by the violence in Charlottesville, VA, and what it represents, the Emmanuel Gospel Center humbly offers some reflections in service to the Church and communities of Boston.

Reflections on Charlottesville

Lead Editor Liza Cagua-Koo, Assistant Director of EGC, with contributions from the EGC Team

As a community of Christians who are grieved by the violence in Charlottesville, VA, and what it represents, the Emmanuel Gospel Center humbly offers some reflections in service to the Church and communities of Boston—the city we love, where God has called us to minister.

We urge our brothers and sisters in Christ to denounce the evil of White supremacy (in all its forms) and affirm that all people are created in the image of God. Indeed, it is our hope that all Bostonians regardless of faith will affirm the dignity and value of every person.

Our Lament

We lament the violence and loss of life in Charlottesville, as well as the larger social situation that allowed such a tragedy to arise.

We lament the fear, personal trials, social conditioning, and isolation that leads some to participate in these public expressions of hatred.

We lament the ways these destructive behaviors hurt most Americans—of every background—as they can encourage more private and public expressions of bigotry, ethnocentrism, and the tendency to hoard resources and opportunities out of fear for the well-being of oneself or one's group.

We lament our country’s long and painful history of prioritizing the welfare of one group over another. We long for this legacy to be increasingly less evident so that we might each stand as equals, not just before God, but before police officers, mortgage brokers, and others in positions that can promote or stifle justice for entire communities.

Our Prayers

We pray for each family—in Charlottesville and beyond—that has experienced the pain of racism, whether acutely through a white supremacy rally or in their daily barriers to opportunity. We ask God for healing, resilience, and courage to continue forward in hope, love, and action.

We pray for those who have been deluded by the lie of White supremacy, and especially those who would say they are followers of Jesus. We pray that Jesus would speak to them by his Spirit and through his Body, the Church. May they in Christ experience freedom from lies they believe about themselves and others, the country, and the world. May they by the Holy Spirit see the choices they can yet make to love others as they love themselves.

We have all these same prayers for ourselves. We ask for God's guidance in the choices we will all make in the future to make another Charlottesville less likely.

Our Calling

Indeed what remains now, what has always remained—even if Charlottesville had never occurred—is our daily calling as Christians, individually and corporately, to relate across lines. We have the privilege and calling to offer a redemptive response to pain, fear, violence, and injustice.

The Church has incomparable resources—in God’s Word, the richness of our faith traditions, and the fullness of God’s Spirit—to bear His love and healing presence. If any community has the shared resources to respond to fear with hope, to injustice with change, to hatred with love, it's the Body of Christ.

Let's commit to go beyond our isolated silos of self-protection or short-sighted action. Let's seek God’s wisdom together, and contribute to Christ's restorative work, all by his grace, in step with his Spirit, and in his name.

ABOUT THE LEad Editor

Jesus captured Liza's heart while at Harvard, and after several years in the private sector leading technology initiatives, she joined urban ministry startup TechMission in 2002. There she launched tech programs and co-directed a youthworker program, all in partnership with local churches. In 2006, Liza joined EGC as senior program director, and has served as assistant director since 2010. A member of Neighborhood Church of Dorchester, Liza learns about growing up in Jesus from being mamá to Jacob & Camila, spouse to Daniel, and daughter to one of the world’s best abuelitas.

Reconciliation in Troubled Times

Our country is deeply divided. What part can we play in healing the nation's racial wounds? And where do we start?

By Rev. Dr. Dean Borgman and Megan Lietz, STM

Includes excerpts from “Reconciliation in Troubled Times”, the inaugural Dean Borgman Lectureship in Practical Theology, Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, March 20, 2017.

Megan Lietz is Director of Race & Christian Community at EGC. Her ministry focus is to help white evangelicals engage respectfully and responsibly in issues of race and racism.

Disclaimer from Megan Lietz: This post is based on a lecture from March, and not written in direct response to the Charlottesville violence. While not stated explicitly in this article, we condemn white supremacy in any form. Many congregations in Boston are working together to develop a unified response. I am in consultation with many Boston-area church and organizational leaders. I look forward to sharing the fruit of those collaborations for action planning.

Our society is deeply divided. These divisions can be found in our national, communal, and church life. From polarization between political parties to disagreements in our response to immigrants and refugees, these divisions are rooted in a fear and distrust of people different from ourselves.

These divisions are not recent phenomena. Rather, they are shaped by our history. How we see ourselves and others, and how we choose to interact with the world around us is colored by what has come before. Unfortunately, much of the division and inequality that has tainted our history was reinforced by faulty anthropologies, psychologies, and theologies that are still with us today in various forms.

We all have a part to play, and the Church should be responding.

Christians today, black or white, wealthy or poor, new or old to this country, must be concerned—be distressed—over our divisions and the inability of our system of economics and government to provide adequate remediation and relief to the suffering.

The God who freed the Hebrews and the American slaves, and who brought relief to the segregated and oppressed under Jim Crow—that God will hear the united cries of American Christians, should we humbly pray for justice.

In the News: Boston Faith Leaders Responding to Charlottesville Violence

Begin with Lament

Lament is a biblical practice, where we acknowledge that things are not right—in the world, nation, community or church—and where we embrace our role and responsibility in it. Lament comes not out of a spirit of complaint. Rather, it invites God into the situation so healing and justice can occur.

For example, laments and confessions came from Moses, Daniel, Nehemiah and other prophets, and Christ on the Cross—for sins they didn’t individually commit. They were earnest, prayers of systemic confession.

Furthermore, of the 150 Psalms, the majority are Psalms of Lament. They provide us examples and guides for the expression of our desire for social, political and church reconciliation.

Biblically, lament is often coupled with confession of how we have contributed to the problem at hand. When Nehemiah is lamenting over the broken walls and associated disgrace that had come upon Jerusalem, he first makes a confession:

LORD, the God of heaven, the great and awesome God, who keeps his covenant of love with those who love him and keep his commandments… I confess the sins we Israelites, including myself and my father’s family, have committed against you. We have acted very wickedly toward you... (Nehemiah 1: 5-7a, NIV)

Nehemiah was not born in the land where such injustice was taking place. He had never participated in the sins he was confessing. But he still confessed the sins of his people and lamented over them, even though he wasn't personally responsible.

We must reflect, lament, and confess today, whether or not we feel personally responsible. We all have a part to play, and we can all go before God to change ourselves and affect healing in our land.

Choose to be Reconcilers

After we lament the division around us, churches must make a choice to engage the division in our midst. Such work is not something that people enter into casually. Rather, it requires intentionality and effort.

Any church or group must first decide that they are committed to biblical social reconciliation. They should be committed to giving this important challenge some time and thought.

Study the Realities and Positive Examples

It's important that we learn more about the division around us and how to be agents of reconciliation. We could begin with understanding the biblical notion of reconciliation, centered on God's reconciling work in Jesus Christ. But we must also gain understanding of sociological, psychological, historical, and theological realities.

Consider the examples of Black churches under slavery, during Jim Crow, the Civil Rights Movement and continued discrimination. Their spirituals, their persistent prayers, and their courageous demonstrations invited collaboration, and slowly produced some measure of social justice. They provide countless examples of how to be agents of reconciliation in a broken and divided world.

We must also seek to understand the perspective of those today who are different from us—this is especially true for white evangelicals. It is very important that we invite the 'others' into conversation, and give them a chance to voice their own stories and hurts.

We can also learn from local organizations. Some of EGC's partners doing reconciliation work include:

Collaborate Across Lines

As we listen, we must also work together with people across dividing lines. We must reach across the chasm of differences and choose some shared Kingdom priorities in which we can invest. As we collaborate with "the other," healing takes place. As we engage with the other, we get glimpses of the coming Kingdom of God.

“It is very important that we invite the ‘others’ who are different from us into conversation, and give them a chance to voice their own stories and hurts.”

Imagine how you might be able to come together with others around shared kingdom values:

spending time with those outside our fortunate situations

hearing the stories of those who have been freed from oppression or rejuvenated, experiencing the hope of the seemingly hopeless

hearing the deep cries and music of the oppressed

seeing victims become survivors and then confident leaders

These are the “now-but-not-yet” experiences of God’s coming Kingdom. When we share mutual love, respect, and inspiration with those who because of our privilege have so much less, we experience something of God’s beloved community—a community of hope.

TAKE ACTION

STOP. REFLECT. PRAY.

What does our city need from its churches?

How might churches collaborate in bringing peace and welfare to the city?

How can seminary educators collaborate with other serving and training organizations working for shalom—the peace and welfare of our city?

JOIN With A REFLECTION/ACTION GROUP

Are you a white evangelical who wants to join with others in a journey of respectful and responsible conversation and engagement of race and racism issues?

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

WHAT DID YOU THINK?

Resource List for Reconciliation in Troubled Times

The following list of resources, recommended by Professor Dean Borgman during his lecture “Reconciliation in Troubled Times,” provides ideas on how one might respond to the racial divisions of our time.

Resource List for Reconciliation in Troubled Times

Compiled by Megan Lietz and Dean Borgman

Prof. Dean Borgman mentioned these resources during his lecture – “Reconciliation in Troubled Times” – as one way that we might learn about how to respond to the division of our time.

The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness by Michelle Alexander

The New Jim Crow is a powerful and provocative book that explains how the racism associated with the Jim Crow era has not been removed, but redesigned and perpetuated through the social ill of mass incarceration. This is a must-read for understanding how systemic racism still has a profound impact on communities of color today.

The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion Jonathan Haidt (2012)

In The Righteous Mind, social scientist Jonathan Haidt argues that our moral, political, and religious positions come more from our “gut feelings” than reason. He considers the implications this has on how we interact with people of differing persuasions and offers perspectives that can help us learn how to cooperate across dividing lines,

Roadmap to Reconciliation: Moving Communities into Unity, Wholeness and Justice by Brenda Salter McNeil

Rev. Dr. Brenda Salter McNeil presents a roadmap describing the journey people go through when working towards biblical reconciliation. This book helps people better understand the journey they may be on and equip themselves to progress on to personal and social transformation.

Toxic Inequality: How America’s Wealth Gap Destroys Mobility, Deepens the Racial Divide & Threatens Our Future by Thomas M. Shapiro

Sociologist Thomas Shapiro explores how the historically high economic inequality our country is experiencing must be understood in light of racial inequality. Together, this combination creates “toxic inequality” that must be named, understood, and addressed together to create a more just society.

Preaching Politics: Proclaiming Jesus in an Age of Money, Power, and Partisanship by Clay Stauffer

How can you address the divisive issues of our time in a politically diverse congregation? Preaching politics talks about how issues that underlie our differences, such as our view of money, materialism, and power, impact faith and can be responded to through the teachings of Jesus.

Exclusion and Embrace: A Theological Exploration of Identity, Otherness and Reconciliation by Miraslav Volf

Croatian theologian, Miraslav Volf, addresses how we see “the other” in a negative light and calls us to move from a position of excluding those who are different from us to embracing them with the love of Jesus. He provides a theology of reconciliation that he believes, when lived, allows people to experience the healing power of the Gospel.

White Evangelicals’ Candid Talk About Race: 6 Takeaways

What happens when a group of white evangelical Christians get together for candid conversation about race issues? Here are six takeaways from a starter conversation on April 1.

White Evangelicals’ Candid Talk About Race: 6 Takeaways

by Megan Lietz

[Last month I posted A Word to White Evangelicals: Now Is The Time To Engage Issues of Race, a call to action for beginning a journey toward respectful and responsible engagement with issues of race. As an action step, I invited white evangelicals to join me for small group conversation on race. The gathering took place April 1, 2017 at EGC. Here’s what we learned together from the experience.]

With little more than a few key questions and a spark of hope, I wasn’t sure how this first conversation would go. Under a surprise April snowstorm, I wasn’t even sure who would show up. But I sensed that God was in this. Having done my part, I was trusting God to do his.

One by one, eight white evangelical Christians filtered in. Men and women of different ages, life experiences, and church backgrounds came to the table with varied levels of awareness about race-related concerns. Against cultural headwinds of complacency and fear, these eight were ready for an open conversation about race.

Stepping Into the River

To frame our time together, I invited each person in the group to use the image of a river to depict their journey toward racial reconciliation. It was my hope that by recalling our experiences together, we could help one another imagine pathways ahead and find the support to move forward.

As people shared parts of their journey, we heard six unique stories. One man’s engagement with race issues began in the 1960s through his observation of racial discrimination at his university and his subsequent positive reaction toward the leadership of the Black Power movement. This got him thinking and eventually led him to visit a black church. One woman began to seriously think about race only weeks before our gathering because of an eye-opening grad school course.

We then used our river-journeys to reflect together on three simple questions: With regard to our engagement in issues of race...

Where are we?

Where do we want to be?

What can we do to move forward?

Takeaways

As group members began to share their experiences wrestling with issues of race and culture, they did so with relief at the opportunity to speak openly. With a life-giving mix of humility and excitement, the group gave voice to the following shared insights.

1. We Remember A Time Before We Were Aware

Each white evangelical in the room remembered a time in their life before they were aware of the magnitude and significance of racial disparities today. As one participant put it, “I didn’t realize there was an issue. It is hard to know there are racial problems when living in racially homogeneous communities.”

Confronting basic, hard realities shifted their perspective, evidenced by comments such as these from various participants:

People of color are not treated the same as white people.

Ethnic injustice was an issue even in biblical times.

People make assumptions about people’s experiences and needs based on the color of their skin.

When people just go with the flow, they are unconsciously agreeing with what is going on.

2. We Have Personal Work To Do

The group broadly agreed on the need for white people to engage in personal learning and engage issues of race more effectively. One participant shared, “There are racist systems (that need to be addressed), but I also need to do a lot of [self-]work.”

Another, who became aware of the profound impact race has on people’s lives more recently, added, “Lack of knowledge keeps me from entering the conversation. I’m still learning, so I’m insecure.” A third participant asserted that white people need to do their learning and self-work both before and during their engagement across racial lines.

3. Story Sharing is Key

Many insights affirmed the power of story sharing to bring awareness and practical guidance. It is a helpful step for us to reflect on our own stories and be willing to be honest and vulnerable. It is essential to become good listeners, giving careful attention to the stories of our brothers and sisters of color. Some of our comments were:

White evangelicals have many things to learn from communities who look different from them.

We should share our own stories about our journey toward racial justice with our fellow white evangelicals.

We should take the posture not of “rescuers,” but of mutual learners.

Sharing our own story can impact others.

Engaging with white people and people of color who are both ahead of and behind us in the journey can be useful in understanding the self-work we need to do.

4. We Need More Skills to Do Hard Conversations Well

The group identified an obstacle in their work around race: limited skill for hard conversations. They attributed the problem to a lack of good models, especially within the white evangelical community, for listening, dialogue, and engaging conflict.

One participant said that white evangelicals are not good at engaging conflict. He went on to explain that, in his experience, people often announce their opinions in ways that shut down conversations rather than invite genuine dialogue. “When people are not listening and are argumentative, it’s difficult to have the conversations that propel people forward in their journey [toward racial reconciliation].”

5. We Need Brave Spaces

When discussing what these leaders would look for in a healthy conversation, they used words like “open,” “humble,” “honest” and “authentic.”

One participant observed, “Lack of [such spaces] keeps us locked in coasting mode or in the status quo.” Brave spaces to engage in uncomfortable conversation are needed for growth.

6. Growth Requires Ongoing Community

These white evangelicals were seeking brave spaces not just for conversation, but to walk with one another in community. One participant declared his need for a “community of inquirers… that address the current social tensions.”

Another added that single events, while helpful in sparking interest and fostering growth, are less effective in supporting lasting transformation. “We need continuity…There needs to be a group who is doing this work over a length of time.”

Pilot Cohort

With a shared longing to experience new ways of listening, dialoguing, and learning in community, the group committed to experiment together as a cohort for a time. The group agreed to use two upcoming meetings to discuss Debby Irving’s book Waking Up White. We will also attend a lecture with the author.

Through this pilot cohort in EGC’s new Race & Christian Community initiative, we aim to:

Create a space where the group can try, fail, learn, and grow.

Practice dialogue that nurtures respectful and responsible engagement around issues of race.

Take Action

Are you a white evangelical Christian interested in a similar, future cohort?

Do you have advice or resources that could help our cohort function more effectively?

Do you want to speak into the development of the Race & Christian Community initiative at EGC?

Please connect with us! We invite the insights of the community and are excited to see where the Lord may lead.

Megan Lietz, M.Div., STM, helps white evangelicals engage respectfully and responsibly with issues of race. She is a Research Associate with EGC's Race & Christian Communities ministry.

Keywords

- #ChurchToo

- 365 Campaign

- ARC Highlights

- ARC Services

- AbNet

- Abolition Network

- Action Guides

- Administration

- Adoption

- Aggressive Procedures

- Andrew Tsou

- Annual Report

- Anti-Gun

- Anti-racism education

- Applied Research

- Applied Research and Consulting

- Ayn DuVoisin

- Balance

- Battered Women

- Berlin

- Bianca Duemling

- Bias

- Biblical Leadership

- Biblical leadership

- Black Church

- Black Church Vitality Project

- Book Recommendations

- Book Reviews

- Book reviews

- Books

- Boston

- Boston 2030

- Boston Church Directory

- Boston Churches

- Boston Education Collaborative

- Boston General

- Boston Globe

- Boston History

- Boston Islamic Center

- Boston Neighborhoods

- Boston Public Schools

- Boston-Berlin

- Brainstorming

- Brazil

- Brazilian

- COVID-19

- CUME

- Cambodian

- Cambodian Church

- Cambridge