BLOG: APPLIED RESEARCH OF EMMANUEL GOSPEL CENTER

History of Revivalism in Boston

Journey with EGC’s Senior Researcher Rudy Mitchell through Boston’s key evangelistic revivals from the First Great Awakening in 1740–1741 through the Billy Graham campaign of 1950. History comes alive as we read how God moved in remarkable ways through gifted evangelists, and we gain a deeper appreciation for Boston’s vibrant Christian history.

History of Revivalism in Boston

Resources for the urban pastor and community leader published by Emmanuel Gospel Center, Boston

Emmanuel Research Review reprint

Issue No. 24 — January/February 2007

by Rudy Mitchell, Senior Researcher, Emmanuel Gospel Center, Boston

Read the full version online here.

Executive Summary

“Revivalism,” according to the Dictionary of Christianity in America, “is the movement that promotes periodic spiritual intensity in church life, during which the unconverted come to Christ and the converted are shaken out of their spiritual lethargy.” David W. Bebbington, professor of history at the University of Stirling in Scotland and a distinguished visiting professor of history at Baylor University, describes revivalism as a strand of evangelicalism, a form of activism (which he identifies as one of evangelicalism’s four key characteristics), where a movement produces conversions “not in ones and twos but en masse.”

Dwight L. Moody revival meeting in Boston

In this 2007 study, EGC’s Senior Researcher Rudy Mitchell traces Boston’s key evangelistic revival movements from the First Great Awakening in Boston in 1740–1741 through the Billy Graham campaign in Boston, starting on New Year’s Eve in 1949. With 23,000 attending services on the Boston Common in 1740 to hear Whitefield (without the benefit of electronic amplification) to an estimated 75,000 gathered at the same spot in 1950 to hear the same Gospel preached by Rev. Billy Graham, the story of revivalism in Boston gives color and texture to the waves of revival.

Rudy introduces us to a few of the key players, remarkable crowds, recorded outcomes, while weaving in familiar faces and places, from Charles Finney, Dwight L. Moody and Billy Sunday to Harvard Yard, Park Street Church and the Boston Garden. We sense history coming alive as we read how God moved in remarkable ways through his gifted evangelists and preachers, and we gain a deeper appreciation for Boston’s vibrant Christian history.

“History of Revivalism in Boston” was first printed in the January/February 2007 issue of the Emmanuel Research Review, Issue 24. It was subsequently published in New England’s Book of Acts, a collection of reports on how God is growing the churches among many people groups and ethnic groups in Greater Boston and beyond.

Table of Contents (with key themes and names added)

First Great Awakening in Boston

Learn More

Read the full version of “History of Revivalism in Boston”

Contact Rudy Mitchell with questions, or to request a printed copy.

Urban Youth Mentoring

he presence of a caring adult in the life of a youth is one of the key factors in influencing a child’s behavior. In addition to parenting, mentoring youth in an urban context provides a highly strategic social-spiritual opportunity to shape future generations and address broader societal issues, including youth violence. In this issue from 2008, EGC Senior Researcher Rudy Mitchell summarizes his research on mentoring youth in an urban context. See also the concluding list of links and resources.

Resources for the urban pastor and community leader published by Emmanuel Gospel Center, Boston

Emmanuel Research Review reprint

Issue No. 41 — September/October 2008

Urban Youth Mentoring

Introduced by Brian Corcoran, Managing Editor, Emmanuel Research Review

The importance of mentoring youth has been identified in numerous studies which collectively establish the fact that the presence of a caring adult in the life of a youth is one of the key factors in influencing a child’s behavior. Therefore, in addition to parenting, mentoring youth in an urban context provides a highly strategic social-spiritual opportunity to shape future generations and address broader societal issues, including youth violence.

In this issue, reprinted from 2008, Rudy Mitchell, Senior Researcher, summarizes his research findings regarding various practical aspects on mentoring youth in an urban context. Rudy’s research draws from both secular and faith-based sources regarding preparation, planning, recruiting, screening, training, matching, support, monitoring, closure, and evaluation of youth mentoring programs. Also included is a selected resource list that provides additional information and examples.

Urban Youth Mentoring

by Rudy Mitchell, Senior Researcher, EGC

Mentoring, in combination with other prevention and intervention strategies, can make a significant contribution to reducing youth violence and delinquency. Research has shown that “the presence of a positive adult role model to supervise and guide a child’s behavior is a key protective factor against violence.”[1]

With careful planning; screening, training, and monitoring of volunteers; and sustained, long-term relationships by the mentors, the lives of at-risk youth can be changed. Christians can be involved by developing faith-based mentoring programs and by serving as mentors in existing programs. In either role they should make good use of the research and resources available in the general field of mentoring.

Preparation and Planning for a New Program

Starting a new mentoring program, even within an established organization, requires careful planning and design. It is important to have the support and active involvement of a board, either existing or newly created.

If you are working in an organization with an existing board, it is still valuable to have a separate advisory committee for the mentoring program.[2] These advisory groups can give guidance on how the initiative will fit in with other programs in the organization and community.

Another early planning step is to assess the needs of youth, survey the services of existing programs, and research the assets of the community. From this research, you can define what type of mentoring services to offer, what specific groups to focus on, and what outcomes may be most needed. One planning tool that can be helpful in defining outcomes is the Logic Model approach.[3]

Other aspects of planning are preparing training materials, developing policies, budgeting/fundraising, and planning record keeping. One must anticipate the need for adequate staffing in addition to recruiting the mentors.

It is important not to underestimate how much support, supervision, and counseling that staff may need to provide. Additional support and resources can be leveraged through collaborative partnerships with other community organizations, with schools, and with businesses.

Recruiting and Screening

When recruiting mentors, it is critical to find individuals who are willing and able to make long-term commitments and who will be dependable and consistent in meeting regularly with the mentee. Research has shown that when relationships break off after a short time, the result may be negative, not just neutral.[4]

During recruitment it is important to clearly present the expected time commitment and frequency of meetings with the mentees, as well as the overall expected duration of the mentoring relationship. Typically mentors are expected to meet with mentees at least four hours a month for one year (or one school year at school-based sites).[5] While the commitments need to be made clear when recruiting participants, the benefits also need to be highlighted.

Mentors should enjoy being with youth, be enthusiastic about life, and be good role models who can inspire youth. Good mentors also should be honest, caring, outgoing, resilient, and empathetic. Mentors will need to be open minded, non-judgmental, and good listeners, not seeking to always direct the agenda and activities.

Of course, mentors need to be carefully screened to be aware of past substance abuse problems, child abuse or molestation problems, criminal convictions, and mental problems. The essential parts of the screening process include a written application, an interview, several references (personal, employer), and criminal background checks (including sex offender and child abuse registries).[6] Some offenses would automatically disqualify a potential mentor, while other past events may raise red flags, but call for good judgment and general guidelines.

For programs not meeting at a fixed site, a home visit is recommended. In the screening process, it is valuable to learn about the motivations of potential mentors to make sure they are not just trying to fill their own unmet needs.

Potential mentors who are long-term members of a congregation and well known by the program staff can move through the approval process somewhat faster, although they still should be evaluated carefully and objectively using the essential and standard process.[7]

Training Mentors

Orientation of mentors can include a presentation of the programs goals, history, and policies. Benefits and hoped for outcomes can be described in ways that don’t generate unrealistic expectations. Orientation can also cover the general nature of the mentoring process.

It is valuable to have good printed literature on the program available at this time. Orientation is often used to recruit and introduce people to a mentoring program before they get involved.

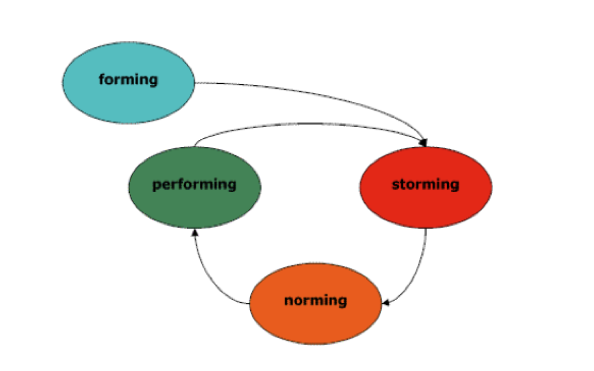

Effective mentoring programs have good mentor training prior to establishing matches and have ongoing training or support. Training can cover communication skills, the stages of a mentoring relationship and how to relate to the mentee’s family. In the first stage of starting a match, the pair may need help in strategies for building trust and rapport, or suggestions for helpful activities.

Young people go through developmental stages which mentors need to be familiar with. Mentoring and other supportive services can be seen as valuable contributors to the overall youth development process. The training can also help mentors with cross-cultural and inter-generational understanding and communication.

Various types of problem situations and needs in the mentee’s life and in the mentoring relationship can be covered in preliminary and ongoing training. Mentors can also become knowledgeable of the social services which are available to help with potential problems.

Training can include ways to guide youth in setting goals, discovering their talents, and making decisions. Growing in these and other life skills, can build self-esteem, especially when appreciated and commended by mentors. It is important for mentors to understand current youth culture and the issues facing youth in the local community.

Some youth may experience emotional problems, and therefore, mentors may need some training in basic counseling skills and knowing when to make suggested referrals. During the training sessions, program policies and responsibilities should be reviewed, including regular reporting and child abuse reporting requirements. Programs with an academic focus may want to include a session on effective tutoring methods.

It is important to have a separate training session for the mentees as well. This will help them understand mentoring, what to expect of their mentor, and give practical suggestions on communication and activities.

Making Matches

The mentoring program needs to develop a weighted list of criteria for matching youth with mentors, criteria that correspond to the program’s priorities. While various criteria can be important, often the general quality of being an understanding listener turns out to make the most difference in developing a relationship.[8]

Basic criteria that can be critical include compatible time schedules and geographic proximity. If the mentoring involves social activities, it can be helpful to have common interests, hobbies, or recreational activities.

In more specialized programs, it may be necessary to match a youth who has certain career interests or academic needs with a mentor from that career field or academic skill set. Other criteria often considered in making matches are gender, language, race, cultural background, and life experiences.

It is also valuable to consider personality and temperament in making a match. Some complex personal qualities may be best sensed by intuition. Depending on the goals and values of the program, some criteria should be weighted more heavily than others.

The parents of the youth are generally given a voice in the process of choosing and approving a mentor. In any case written parental permission for general participation is necessary. Programs can also consider input and preferences from mentees and mentors.

Once the match is decided, the program should arrange a formal meeting for introduction at the organizational site. This meeting can include some icebreakers or activities, and can include a group of newly matched pairs.

Typically the best initial foundation of a good relationship is trust and friendship rather than achieving goals and tasks. “Research has found that mentoring relationships that focus on trying to change the young person too quickly are less appealing to youth and less effective. Relationships focused on developing trust and friendship are almost always more beneficial.”[9] Thus the initial activities and focus should seek to foster communication, trust, and rapport, rather than just accomplish tasks.

Ongoing Support, Training, and Monitoring

Ongoing support is one of the most important elements in a successful mentoring program. Mentors should be contacted within two weeks of the beginning of the relationship.[10] Program staff should then continue to maintain regular, personal communication weekly, bi-weekly, or monthly with the mentors.

In order to give adequate support it is recommended that a 20 to 1 ratio be maintained between mentors and support staff.[11] These personal contacts can help intervene to clear up misunderstandings, provide insights regarding cultural differences, and give encouragement.

In addition to good communication, the program can arrange regular meetings of mentors for discussion of problems, sharing ideas, and giving recognition and appreciation. Some of these mentor meetings can include additional training on issues facing a number of the mentors or youth.

Experienced mentors can help in training newer mentors. Online support groups could also be used to share ideas, ask questions, and discuss issues. Support staff may occasionally need to work out a new match, if the original match has been given plenty of time and effort, but is just not working out.

Closure and Evaluation

The mentoring program needs to have flexible procedures and support services to handle the closure of a match. A mentoring relationship may end naturally as a school year ends, or when one of the pair moves away. However, it may also end because of problems, incompatibility, disinterest, or violation of rules.

Because of the variety of reasons relationships end, the program needs to tailor its approaches to giving closure and support to the youth, mentor, and the family. It is just as important for the match to have a good closure as to have a good beginning.

Exit interviews are often used in closing a relationship. These may involve the mentor and mentee together or separately. Generally there should be a meeting with the family as well. These meetings can be a constructive learning experience, as reasons for the termination are clarified and discussed in a positive way. The youth should be encouraged to share feelings about what went well and what could have been improved.

It is helpful for the mentor and mentee to share what they enjoyed most in the relationship. When the match ends because the mentor is no longer able to continue, it is especially important to reassure the youth that the ending is not due to anything he or she did. Where appropriate, the staff can discuss possible future matches in the current program, or elsewhere (if one participant is moving).

Exit interviews can also play a valuable role in evaluation. Program evaluation can be done by your own staff, using or adapting the many survey tools available,[12] or by an outside evaluator (possibly drawing on an university department or a grad student intern).

One can evaluate the effectiveness of various processes of implementing the overall program, but it is even more important to evaluate the goals and outcomes you have established for and with the youth. These outcomes can guide the choice of measures and data needed for evaluation.

Typically, a baseline of information should be gathered when youth begin, and then progress can be measured after the matches have been going at least six months to a year.[13] If possible, try to also get information on a comparable group which was not mentored. Data sources may include the youth, mentors, family, school records, teachers, and police.

Don’t assume your program was the only cause of any improvement. However, as you follow the guidelines for effective practices and work collaboratively with the youths’ families, other organizations serving youth, and the schools, you can expect to see a positive difference in the lives of young people.

Footnotes

1 Timothy N. Thornton., Carole A. Craf, Linda L. Dahlberg, Barbara S. Lynch, and Katie Baer, Youth Violence Prevention: A Sourcebook for Community Action (New York: Novinka Books, 2006), 150.

2 Michael Garringer and Pattti McRae, editors. Foundations of Successful Youth Mentoring, rev. ed. (Washington, D. C.: Hamilton Fish Institute and the National Mentoring Center, 2007), 8.

3 W.K. Kellogg Foundation, Logic Model Development Guide, http://www.wkkf.org/Pubs/Tools/Evaluation/Pub3669.pdf (14 Nov. 2008).

4 D.L. DuBois, B.E. Holloway, J.C. Valentine, and H. Cooper. “Effectiveness of Mentoring Programs for Youth: A Meta-Analytic Review.” American Journal of Community Psychology 30, no. 2 (April 2002):157-197.

5 National Mentoring Partnership, How to Build a Successful Mentoring Program Using the Elements of Effective Practice (Alexandria, Vir.: National Mentoring Partnership, 2005), 10.

6 Garringer and McRae, 29.

7 Shawn Bauldry, and Tracey A. Hartmann, The Promise and Challenge of Mentoring High-Risk Youth: Findings from the National Faith-Based Initiative (Philadelphia: Public/Private Ventures, n.d.), 14-15.

8 Maureen A. Buckley and Sandra Hundley Zimmermann, Mentoring Children and Adolescents: A Guide to the Issues (Westport, Conn.: Praeger Publishers, 2003), 43.

9 Bauldry, and Hartmann, The Promise and Challenge of Mentoring High-Risk Youth, 20.

10 National Mentoring Partnership, How to Build a Successful Mentoring Program Using the Elements of Effective Practice, 105.

11 Timothy N. Thornton., et al, Youth Violence Prevention, 171.

12 National Mentoring Partnership, How to Build a Successful Mentoring Program Using the Elements of Effective Practice, 171-172. 13 Garringer and McRae, 58.

Resources and Links

Buckley, Maureen A., and Sandra Hundley Zimmerman. Mentoring Children and Adolescents: A Guide to the Issues. Contemporary Youth Issues. Westport, Conn.: Praeger Publishers, 2003.

This is a practical and comprehensive handbook which includes sample mentor and mentee applications, a full sample grant proposal/program design, and detailed quality standards for effective programs. The authors provide an annotated list of print and non-print resources, as well as detailed information on state and national organizations and key people. Several chapters give an overview of practical aspects of formal mentoring programs and summarize facts and research studies.

Dortch, Thomas W., Jr., and The 100 Black Men of America, Inc. The Miracles of Mentoring: How to Encourage and Lead Future Generations. New York: Broadway Books, 2001.

Drury, K.W., editor. Successful Youth Mentoring: Twenty-four Practical Sessions to Impact Kid’s Lives. Loveland, Calif.: Group Publishing, 1998.

DuBois, D.L., B.E. Holloway, J.C. Valentine, and H. Cooper. “Effectiveness of Mentoring Programs for Youth: A Meta-Analytic Review.” American Journal of Community Psychology 30, no. 2 (April 2002):157-197.

The authors reviewed 55 research evaluations of mentoring programs. They found that disadvantaged and at-risk youth benefit most from mentoring. Significant positive effects depend on the use of best practices and developing strong relationships. Poorly implemented programs can have a negative effect on youth; therefore, it is important for programs to use effective methods of planning, implementation, and evaluation.

Dubois, David L., and Michael J. Karcher, editors. Handbook of Youth Mentoring. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications, 2005.

This is one of the most comprehensive recent works on the theory, research, and practice of mentoring youth. Under the section on theory and frameworks, Jean Rhodes presents a theoretical model of mentoring where relationships of mutuality, trust, and empathy promote social-emotional, cognitive, and identity development. For formal mentoring programs, the handbook gives useful material on developing and evaluating a program, and on recruiting and sustaining volunteers. In addition to covering various types of mentoring (natural, cross-age, intergenerational, e- mentoring), the book also considers mentoring in various contexts (schools, work, after-school, faith-based organizations, and international settings), and with specific groups (at-risk students, juvenile offenders, gifted youth, pregnant/parenting adolescents, abused youth, and youth with disabilities).

Freedman, Marc. The Kindness of Strangers: Adult Mentors, Urban Youth, and the New Voluntarism. Revised ed. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Over three hundred interviews were conducted to produce this important work on urban youth mentoring. It distills guidelines and principles for effective mentoring programs and gives overviews of some mentoring efforts around the country. While realistically looking at pitfalls and problems, the book offers a hopeful perspective on mentoring as one important part of the solution to youth violence and other problems.

Hall, Horace R. Mentoring Young Men of Color: Meeting the Needs of African American and Latino Students. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield Education, 2006.

Hall advocates mentoring and other strategies to channel care and concern for young men to enable them to reach their potential despite the challenges they face.

National Mentoring Center—http://www.nwrel.org/mentoring/index.php

The National Mentoring Center (NMC) has been serving youth mentoring programs of all types since 1999. Originally created by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP), the National Mentoring Center offers training, resources, and online information services to the entire mentoring field. The NMC now houses the LEARNS project, which provides training and technical assistance to mentoring projects supported by the Corporation for National and Community Service. The NMC also works in partnership with EMT Associates to manage the Mentoring Resource Center.

Foundations of Successful Youth Mentoring is the Center’s cornerstone resource for developing all types of youth mentoring programs across a variety of settings. It is a useful resource for start-up efforts and established programs alike. This 114 page guidebook is available free from the website, and covers all aspects of developing a mentoring program, with included charts and sample forms.

National Mentoring Partnership/MENTOR—www.mentoring.org

An advocate and resource for the expansion of quality mentoring initiatives nationwide. This networking organization builds and supports state mentoring partnerships, sponsors the National Mentoring Institute, develops resources like the Elements of Effective Practice, and encourages research and support for mentoring. The website makes available many great resources including:

Elements of Effective Practice, guidelines and detailed action steps developed by leading national authorities on mentoring. They were recently revised, taking into account solid research to help mentoring programs plan effective organizations that will nurture quality, enduring mentoring relationships. Available free at: http://www.mentoring.org/downloads/mentoring_411.pdf.

How to Build a Successful Mentoring Program Using the Elements of Effective Practice. While the previous resource provides a detailed outline, this handbook discusses in detail the considerations and methods of carrying out the steps needed to develop a quality mentoring program. It covers design and planning, managing, implementing, and evaluating the program. Many specific forms, handouts, lists, and guidelines are included, esp. on the CD. This 188 page “toolkit” handbook can be downloaded free at www.mentoring.org/eeptoolkit or purchased in print and CD format.

The Mass Mentoring Partnership (Mass Mentoring)—www.massmentors.org is the state partner of the National Mentoring partnership.

Rhodes, Jean. E. Stand By Me: The Risks and Rewards of Mentoring Today’s Youth. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2002.

Rhodes draws on her own research and also an analysis of research by Public Private Ventures to inform her well-written study. Well trained mentors who develop good, long-term mentoring relationships can make a difference in the lives of at-risk youth by improving their social skills, develop their thinking and academic skills through dialog, and by serving as advocates and role models. She also provides cautions about the risks of ineffective and damaging mentoring relationships.

Sipe, Cynthia L. Mentoring: A Synthesis of P/PV’s Research, 1988-1995. Philadelphia: Public/Private Ventures, 1996. Available as a free download at: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org.

In addition to reviewing the major findings of Public/Private Ventures’ mentoring research, this synthesis summarizes ten different research reports of the period.

Thornton, T. N., C.A. Craf, L. L. Dahlberg, B.S. Lynch, and K. Baer. Youth Violence Prevention: A Sourcebook for Community Action. New York: Novinka Books, 2006. See pages 149-192.

One of the four major strategies to prevent youth violence covered in this sourcebook is mentoring. The material here is especially helpful because it reviews and summarizes a wide range of research and resources. It surveys community-based and site-based mentoring with reviews of research on Big Brothers/Big Sisters and the Norwalk Mentor Program. It deals with staff and mentor recruiting and training principles and resources, goal setting, activities, and evaluation. The guide to books, research, training materials, and organizations offers many useful resources.

Find more youth mentoring resources at Culture and Youth Studies: http://cultureandyouth.org/mentoring/

Take Action

Understanding Boston's Quiet Revival

What is the Quiet Revival? Fifty years ago, a church planting movement quietly took root in Boston. Since then, the number of churches within the city limits of Boston has nearly doubled. How did this happen? Is it really a revival? Why is it called "quiet?" EGC's senior writer, Steve Daman, gives us an overview of the Quiet Revival, suggests a definition, and points to areas for further study.

Resources for the urban pastor and community leader published by Emmanuel Gospel Center, Boston

Emmanuel Research Review reprint

Issue No. 94 — December 2013 - January 2014

Introduced by Brian Corcoran

Managing Editor, Emmanuel Research Review

Boston’s Quiet Revival started nearly 50 years ago, bringing an unprecedented and sustained period of new church planting across the city. In 1993, when the Applied Research team at the Emmanuel Gospel Center (EGC) began to analyze our latest church survey statistics and realized how extensive church planting had been during the previous 25 years, resulting in a 50% net increase in the number of churches, Doug Hall, president, coined the term, “Quiet Revival.” This movement, he later wrote, is “a highly interrelated social/spiritual system” that does not function “in a way that lends itself to a mechanistic form of analysis.” That is why, he theorized, we could not see it for years.* Perhaps because it was so hard to see, it also has been hard to understand all that is meant by the term.

One of the most obvious evidences of the Quiet Revival is that the number of churches within the city limits of Boston has nearly doubled since 1965. Starting with that one piece of evidence, Steve Daman, EGC’s senior writer, has been working on a descriptive definition of the Quiet Revival. It is our hope that launching out from this discussion and the questions Steve raises, more people can grow toward shared understanding and enter into meaningful dialog about this amazing work of God. We also hope that more can participate in fruitful ministries that are better aligned with what God has done and is continuing to do in Boston today. And thirdly, we want to inspire thoughtful scholars who will identify intriguing puzzles which will prompt additional study.

*Hall, Douglas A. and Judy Hall. “Two Secrets of the Quiet Revival.” New England’s Book of Acts. Emmanuel Gospel Center, 2007. Accessed 01/24/14.

What is the Quiet Revival?

by Steve Daman, Senior Writer, Emmanuel Gospel Center

What is the Quiet Revival? Here is a working definition:

The Quiet Revival is an unprecedented and sustained period of Christian growth in the city of Boston beginning in 1965 and persisting for nearly five decades so far.

What questions come to mind when you read this description? To start, why did we choose the words: “unprecedented”, “sustained”, “Christian growth”, and “1965”? Can we defend or define these terms? Or what about the terms “revival” and “quiet”? What do we mean? And what might happen to our definition if the revival, if it is a revival, “persists” for more than “five decades”? How will we know if it ends?

These are great questions. But before we try to answer a few of them, let’s add more flesh to the bones by describing some of the outcomes that those who recognize the Quiet Revival attribute to this movement. These outcomes help us to ponder both the scope and nature of the movement:

The number of churches in Boston has nearly doubled since 1965, though the city’s population is about the same now as then.

Today, Boston’s Christian church community is characterized by a growing unity, increased prayer, maturing church systems, and a strong and trained leadership.

The spiritual vitality of churches birthed during the Quiet Revival has spread, igniting additional church development and social ministries in the region and across the globe.

From these we can infer more questions, but the overarching one is this: “How do we know?” Surely we can verify the numbers and defend the first statement regarding the number of churches, but the following assertions are harder to verify. How do we know there is “a growing unity, increased prayer, maturing church systems, and a strong and trained leadership”? The implication is that these characteristics are valid evidences for a revival and that they have appeared or grown since the start of the Quiet Revival. Further, has “the spiritual vitality of churches birthed during the Quiet Revival… spread, igniting additional church development and social ministries in the region and across the globe”? What evidence is there? If these assertions are true, then indeed we have seen an amazing work of God in Boston, and we would do well to carefully consider how that reality shapes what we think about Boston, what we think about the Church in Boston, and how we go about our work in this particular field.

Numbers tell the story

The chief indicator of the Quiet Revival is the growth in the number of new churches planted in Boston since 1965. The Emmanuel Gospel Center (EGC) began counting churches in 1969 when we identified 300 Christian churches within Boston city limits. The Center conducted additional surveys in 1975, 1989, and 1993.1 When we completed our 1993 survey, our statistics showed that during the 24 years from 1969 to 1993, the total number of churches in the city had increased by 50%, even after it overcame a 23% loss of mainline Protestant churches and some decline among Roman Catholic churches.

That data point got our attention. At a time when people were asking us, “Why is the Church in Boston dying?” the numbers told a very different story.

Just four years before the discovery, when we published the first Boston Church Directory in 1989, we saw the numbers rising. EGC President Doug Hall recalls, “As we completed the 1989 directory and began to compile the figures, we were amazed to discover that something very significant was occurring. But it wasn’t until our next update in 1993 that we knew conclusively that the number of churches had grown—and not by just 30 percent as we had first thought, but by 50 percent! We had been part of a revival and did not know it.”2 It was then Doug Hall coined the term, the Quiet Revival.

Fifty-five new churches had been planted in the four years since the previous survey, bringing the 1993 total to 459. EGC’s Senior Researcher Rudy Mitchell wrote at the time, “Since 1968 at least 207 new churches have started in Boston. This is undoubtedly more new church starts than in any other 25-year period in Boston’s history.”3

In the 20 years since then, church planting has continued at a robust rate. EGC’s count for 2010 was 575, showing a net gain since the start of the Quiet Revival of 257 new churches. The Applied Research staff at the Center is now in the beginning stages of a new city-wide church survey. Already we have added more than 50 new churches to our list (planted between 2008 and 2014) while at the same time we see that a number of churches have closed, moved, or merged. It seems likely from these early indicators that the number of churches in Boston has continued to increase, and the total for 2014 will be larger than the 575 we counted in 2010, getting us even closer to that seductive “doubling” of the number since 1965, when there were 318 churches.4

Regardless of where we go with our definition, what terms we use, and what else we may discover about the churches in Boston, this one fact is enough to tell us that God has done something significant in this city. We have seen a church-planting movement that has crossed culture, language, race, neighborhood, denomination, economic levels, and educational qualifications, something that no organization, program, or human institution could ever accomplish in its own strength.

Defining terms

Let’s return to our working definition and consider its parts.

The Quiet Revival is an unprecedented and sustained period of Christian growth in the city of Boston beginning in 1965 and persisting for nearly five decades so far.

“Quiet”

The term “quiet” works well here because of its obvious opposite. We can envision “noisy” revivals, very emotional and exciting local events where participants may experience the presence of the Holy Spirit in powerful ways. If something like that is our mental model of revival, then to classify any revival as “quiet” immediately gets our attention and tempts us to think that maybe something different is going on here. How or why could a revival be quiet?

In this case, the term “quiet” points to the initially invisible nature of this revival. Doug Hall used the term “invisible Church” in 1993, writing that researchers tend “to document the highly visible information that is pertinent to Boston. We also want to go beyond the obvious developments to discover a Christianity that is hidden, and that is characteristically urban. By looking past the obvious, we have discovered the ‘invisible Church.’”5

An uncomfortable but important question to ask is, “From whom was it hidden?” If we are talking about a church movement starting in 1965, we can assume that the majority of people who may have had an interest in counting all the churches in the city—people like missiological researchers, denominational leaders, or seminary professors—were probably predominantly mainline or evangelical white people. This church-planting movement was hidden, EGC’s Executive Director Jeff Bass says, because “the growth was happening in non-mainline systems, non-English speaking systems, denominations you have never heard of, churches that meet in storefronts, churches that meet on Sunday afternoons.”6

Jeff points out that EGC had been working among immigrant churches since the 1960s, recognizing that God was at work in those communities. “We felt the vitality of the Church in the non-English speaking immigrant communities,” he says. Through close relationships with leaders from different communities, beginning in the 1980s, EGC was asked to help provide a platform for ministers-at-large who would serve broadly among the Brazilian, the Haitian, and the Latino churches. “These were growing communities, but even then,” Jeff says, “these communities weren’t seen by the whole Church as significant, so there was still this old way of looking at things.”7 Even though EGC became totally immersed in these diverse living systems, we were also blind to the full scale of what God was doing at the time.

Gregg Detwiler, director of Intercultural Ministries at EGC, calls this blindness “a learning disability,” and says that many Christian leaders missed seeing the Quiet Revival in Boston through sociological oversight. “By sociological oversight, I am pointing to the human tendency toward ethnocentrism. Ethnocentrism is a learning disability of evaluating reality from our own overly dominant ethnic or cultural perspective. We are all susceptible to this malady, which clouds our ability to see clearly. The reason many missed seeing the Quiet Revival in Boston was because they were not in relationship with where Kingdom growth was occurring in the city—namely, among the many and varied ethnic groups.”8

The pervasive mental model of what the Church in Boston looks like, at least from the perspective of white evangelicals, needs major revision. To open our arms wide to the people of God, to embrace the whole Body of Christ, whether we are white or people of color, we all must humble ourselves, continually repenting of our tendency toward prejudice, and we must learn to look for the places where God, through his Holy Spirit, is at work in our city today.

We not only suffer from sociological oversight, Gregg says, but we also suffer from theological oversight. “By theological oversight I mean not seeing the city and the city church in a positive biblical light,” he writes. “All too often the city is viewed only as a place of darkness and sin, rather than a strategic place where God does His redeeming work and exports it to the nations.” The majority culture, especially the suburban culture, found it hard to imagine God’s work was bursting at the seams in the inner city. Theological oversight may also suggest having a view of the Church that does not embrace the full counsel of God. If some Christians do not look like folks in my church, or they don’t worship in the same way, or they emphasize different portions of Scripture, are they still part of the Body of Christ? To effectively serve the Church in Boston, the Emmanuel Gospel Center purposes to be careful about the ways we subconsciously set boundaries around the idea of church. We are learning to define “church” to include all those who love the Lord Jesus Christ, who have a high view of Scripture, and who wholeheartedly agree to the historic creeds.

If we can learn to see the whole Church with open eyes, maybe we can also learn to hear the Quiet Revival with open ears, though many living things are “quiet.” A flower garden makes little noise. You cannot hear a pumpkin grow. So, too, the Church in Boston has grown mightily and quietly at the same time. “Whoever has ears to hear,” our Lord said, “let them hear” (Mark. 4:9 NIV).

“Revival”

What is revival? A definition would certainly be helpful, but one is difficult to come by. There are perhaps as many definitions as there are denominations. All of them carry some emotional charge or some room for interpretation. Yet the word “revival” does not appear in the Bible. As we ask the question: “Is the Quiet Revival really a revival?” we need to find a way to reach agreement. What are we looking for? What are the characteristics of a true revival?

Tim Keller, founding pastor of Redeemer Presbyterian Church in New York City, has written on the subject of revival and offers this simple definition: “Revival is an intensification of the ordinary operations of the work of the Holy Spirit.” Keller goes on to say it is “a time when the ordinary operations of the Holy Spirit—not signs and wonders, but the conviction of sin, conversion, assurance of salvation and a sense of the reality of Jesus Christ on the heart—are intensified, so that you see growth in the quality of the faith in the people in your church, and a great growth in numbers and conversions as well.”9 This idea of intensification of the ordinary is helpful. If church planting is ordinary, from an ecclesiological frame of reference, then robust church planting would be an intensification of the ordinary, and thus a work of God.

David Bebbington, professor of history at the University of Stirling in Scotland, states in Victorian Religious Revivals: Culture and Piety in Local and Global Contexts, that there are several types or “patterns” of revival. First, revival commonly means “an apparently spontaneous event in a congregation,” usually marked by repentance and conversions. Secondly, it means “a planned mission in a congregation or town.” This practice is called revivalism, he notes, “to distinguish it from the traditional style of unprompted awakenings.” Bebbington’s third pattern is “an episode, mainly spontaneous, affecting a larger area than a single congregation.” His fourth category he calls an awakening, which is “a development in a culture at large, usually being both wider and longer than other episodes of this kind.” In summary, “revivals have taken a variety of forms, spontaneous or planned, small-scale or vast.”10

These are helpful categories. Using Bebbington’s analysis, we would say the Quiet Revival definitely does not fit his first and second patterns, but rather fits into his third and fourth patterns. The Quiet Revival was mainly spontaneous. While we can assume there was planning involved in every individual church plant, the movement itself was too broad and diverse to be the result of any one person’s or one organization’s plan. The Quiet Revival seems to have emerged from the various immigrant communities across the city simultaneously, and has been, as Bebbington says, “both wider and longer than other episodes of this kind.” The Quiet Revival was and is vast, city-wide, regional, and not small-scale.

Since at least the 1970s, and maybe before that, many people have proclaimed that New England or Boston would be a center or catalyst for a world-wide revival, or possibly one final revival before Christ’s return. But even that prophecy, impossible to substantiate, is hard to define. What would that global revival actually look like? Scripture seems to affirm that the Church grows best under persecution. That is certainly true today. Missionary author and professor Nik Ripken11 has chronicled the stories of Christians living in countries where Christianity is outlawed and gives remarkable testimony to the ways the Church thrives under persecution. Yet it would seem that what people describe or hope for when they talk about revival in Boston has nothing to do with persecution or hardship.

Dr. Roberto Miranda, senior pastor of Congregación León de Judá in Boston, has revival on his mind. In addition to a recent blog on his church’s website reviewing a book about the Scottish and Welsh revivals, he spoke in 2007 on his vision for revival in New England.12 Despite the fact that few agree on what revival looks like and what we should expect, should God send even more revival to Boston, the subject is always close at hand.

Again, it is interesting that so many Christians would miss seeing the Quiet Revival when there were so many voices in the Church predicting a Boston revival during the same time frame. Many of them, no doubt, are still looking.

“unprecedented”

As mentioned earlier, EGC’s Senior Researcher Rudy Mitchell wrote in 1993, “Since 1968 at least 207 new churches have started in Boston. This is undoubtedly more new church starts than in any other 25-year period in Boston’s history.” What Rudy wrote in 1993 continues to be true today, as it appears the rate of church planting has not fallen off since then. Never before has Boston seen such a wave of new church development. God, indeed, has been good to Boston.

“sustained”

The EGC Applied Research team will be able to assess whether or not the Quiet Revival church planting movement is continuing once we complete our 2014 survey. It is remarkable that the Quiet Revival has continued for as long as it has. The next question to consider is “why?” What are the factors that have allowed this movement to continue for so long unabated? What gives it fuel? We may also want to know who are the church planters today, and are they in some way being energized by what has gone on during the previous five decades?

Rev. Ralph Kee, a veteran Boston church planter, and animator of the Greater Boston Church Planting Collaborative, wants to see new churches be “churches that plant churches that plant churches.” He says we need to put into the DNA of a new church this idea that multiplication is normal and expected. He has documented the genealogical tree of one Boston church planted in 1971 that has since given birth to hundreds of known daughter and granddaughter and great-granddaughter churches. Is the Quiet Revival sustained because Boston’s newest churches naturally multiply?

Another reason the Quiet Revival has continued for decades may be the introduction of a contextualized urban seminary into the city as the Quiet Revival was gaining momentum. EGC recently published an interview with Rev. Eldin Villafañe, Ph.D., the founding director of the Center for Urban Ministerial Education (CUME), the Boston campus of Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, and a professor of Christian social ethics at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary. Dr. Villafañe confirmed CUME was shaped by the Quiet Revival. But as both are interconnected living systems, CUME also shaped the revival, giving it depth and breadth.

“One of the problems with revivals anywhere,” Dr. Villafañe points out, “is oftentimes you have good strong evangelism that begins to grows a church, but the growth does not come with trained leadership, educated biblically and theologically. You can have all kinds of problems. Besides heresy, you can have recidivism, people going back to their old ways. The beautiful thing about the Quiet Revival is that just as it begins to flourish, CUME is coming aboard.”13

CUME was in place as a contextualized urban seminary to “backfill theology into the revival,” as Jeff Bass describes it, training thousands of local, urban leaders since 1976, with 300 students now attending each year.

“Christian growth”

We use the words “Christian growth” rather than “church growth” for a reason. We want to move our attention beyond the numbers of churches to begin to comprehend how these new churches may have influenced the city. Surely it is not only the number of churches that has grown. The number of people attending churches has also grown. One of the goals of the EGC Applied Research team is to document the number of people attending Boston’s churches today.14

But as we look beyond the number of churches and the number of people in those churches, we also want to see how these people have impacted the city. “Christians collectively make a difference in society,”15 says Dana Robert, director of the Center for Global Christianity and Mission at Boston University. Exploring and documenting the ways that Christians in Boston have made an impact on the city, showing ways the city has changed during the Quiet Revival, would be an important and valuable contribution to the ongoing study of Christianity in Boston.

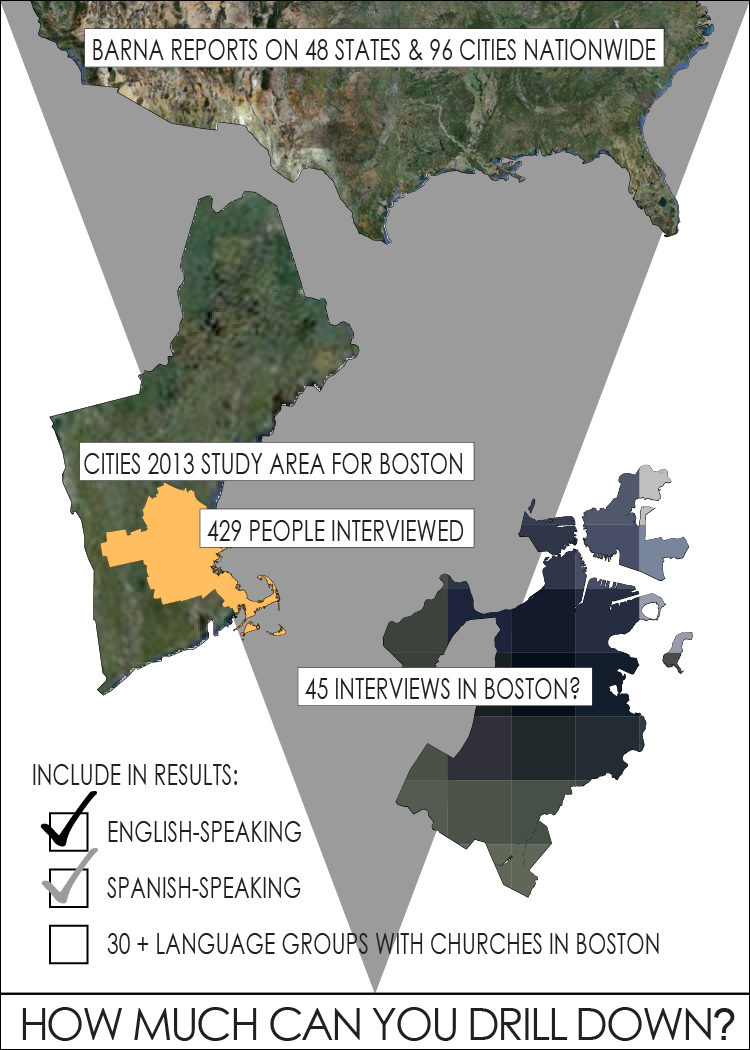

“city of Boston”

We mean something very specific when we say “the city of Boston.” As Rudy Mitchell pointed out in the April 2013 Issue of the Review, one needs to understand exactly what geographical boundaries a particular study has in mind. “Boston” may mean different things. “This could range from the named city’s official city limits, to its county, metropolitan statistical area, or even to a media area covering several surrounding states.” Regarding the Quiet Revival, we mean Boston’s official city limits which today include distinct neighborhoods such as Roxbury, Dorchester, Jamaica Plain, East Boston, etc., all part of the city itself.

Boston’s boundaries have not changed during the Quiet Revival, but when we have occasion to look further back into history and consider the churches active in Boston in previous generations, we need to adjust the figures according the where the city’s boundary lines fell at different points in history as communities were absorbed into Boston or as new land was claimed from the sea.

EGC’s data gathering and analysis is, for the most part, restricted to the city of Boston, as we have described it. However, the Center’s work through our various programs often extends beyond these boundaries through relational networks, and we see the same dynamics at work in other urban areas in Greater Boston and beyond. It would be interesting to compare the patterns of new church development among immigrant populations in these other cities with what we are learning in Boston. There is, for example, some very interesting work being done on New York City’s churches on a Web site called “A Journey Through NYC Religions” (http://www.nycreligion.info/).

“1965”

We chose 1965 as a start date for the Quiet Revival for two reasons. First, there seems to be a change in the rate of new church plants in Boston starting in 1965. Of the 575 churches active in Boston in 2010, 17 were founded throughout the 1950s, showing a rate of less than 2 per year. Seven more started between 1960 and 1963 while none were founded in 1964, still progressing at a rate of less than 2 per year. Then, over the next five years, from 1965 to 1969, 20 of today’s churches were planted (averaging 4 per year); about 40 more were launched in the 1970s (still 4 per year), 60 in the 1980s (averaging 6 per year), 70 in the 1990s (averaging 7 per year), and 60 in the 2000s (6 per year). Again, we are counting only the churches that remain until today. A large number of others were started and either closed or merged with other churches, so the actual number of new churches planted each year was higher.

Another reason for choosing 1965 as the start date was that the Immigration Act of 1965 opened the door to thousands of new immigrants moving into Boston. Our research shows that the majority of Boston’s new churches were started by Boston’s newest residents, and that that trend continued for years. For example, of the 100 churches planted between 2000 and 2005, about 15% were Hispanic, 10% were Haitian, and 6% were Brazilian. At least 5% were Asian and another 7% were African. Not more than 14 of the 100 churches planted during those years were primarily Anglo or Anglo/multiethnic. The remaining 40 to 45% of new churches were African American, Caribbean or of some other ethnic identity.

Throughout the first few decades of the Quiet Revival, most, but not all new church development occurred within the new immigrant communities. At the same time many immigrant communities experienced significant growth in Boston, the African American population was also growing, showing an increase of 40% between 1970 and 1990. Between 1965 and 1993, although 39 African American churches closed their doors, well over 100 new ones started, for a net increase of about 75 churches. Among today’s total of 140 congregations with an African American identity, 57 were planted during those early years of the Quiet Revival between 1965 and 1993. Many of these churches have grown under skilled leadership to be counted among the most influential congregations in Boston, and new Black churches continue to emerge.

The year 1965 was a year of much change. While we point to these two specific reasons for picking this start date for the Quiet Revival (the change in the rate of church planting in Boston and the Immigration Act of 1965), there were other movements at play. A charismatic renewal began to sweep across the country at that time starting in the Catholic and Episcopal communities on the West Coast. Close on its heels was the Jesus Movement. Vatican II, which was a multi-year conference, coincidentally closed in 1965, bringing sweeping changes to the Roman Catholic community. Socially, the civil rights movement was front and center during those years.

It seems obvious from the evidence of who was planting churches that one of the main influencing factors was the Pentecostal movement among the immigrant communities. It may also be helpful to explore some of the other cultural movements occurring simultaneously to see if other influences helped to fan the flames. We may discover that in addition to immigration factors, various other streams—whether cultural, Diaspora, theological, or social—were used by God to facilitate the growth of this movement.

Boston’s population

Some may wrongly assume that the growing number of new churches in Boston must relate to a growing population. This is certainly not true of Boston. The population of the city of Boston was 616,326 in 1965 and forty-five years later, in 2010, was very nearly the same at 617,594. During those years, however, the population actually declined by more than 50,000 to 562,994 in 1980. This shows that this remarkable increase in the number of churches is not the result of a much larger population.

While the population total was about the same in 2010 as it was in 1965, the makeup of that population has changed dramatically through immigration and migration, and this is a very significant factor in understanding the Quiet Revival.

One issue that still needs to be addressed is Boston’s church attendance in proportion to the population. Based on our current research and over 40 years’ experience studying Boston’s church systems, we estimate that this number has increased from about 3% to as much as perhaps 15% during this period. EGC is preparing to conduct additional comprehensive research to accurately assess the percentage of Bostonians who attend churches.

The other indicators

How do we know there is “a growing unity, increased prayer, maturing church systems, and a strong and trained leadership”? What evidence is there that “the spiritual vitality of churches birthed during the Quiet Revival has spread, igniting additional church development and social ministries in the region and across the globe”?

The work required to clearly document and defend these statements is daunting. These issues are important to the Applied Research staff, and we welcome assistance from interested scholars and researchers to help us further develop these analyses. In a future edition of this journal, we may be able to start to bring together some evidences to support these assertions, but we do not have the time or space to do more than to give a few examples here.

We have compiled information relevant to each of these specific areas. For example, we have evidence of more expressions of unity among churches and church leaders, such as the Fellowship of Haitian Evangelical Pastors of New England. We continue to discover more collaborative networks, and more prayer movements, such as the annual Greater Boston Prayer Summit for pastors, which began in 2000. We can point to churches and church systems that have grown to maturity and are bearing much fruit in both the proclamation of the Gospel and in social ministries, such as the Black Ministerial Alliance of Greater Boston. We are aware of several excellent organizations and schools where leaders may be trained and grow in their skills, in knowledge, and in collaborative ministry.16

For the staff of EGC, this is all far more than an academic exercise. We work in this city and many of us make it our home as well. It is a vibrant and exciting place to be, precisely because the Quiet Revival has changed this city on so many levels. Doug and Judy Hall, EGC’s president and assistant to the president, have been serving in Boston at EGC since 1964, and they have observed these changes. A number of others on our staff have also been working among these churches for decades, including Senior Researcher Rudy Mitchell, who started studying churches and neighborhoods in 1976. Doug Hall says that in the 1960s, it was hard to recommend many good churches, ones for which you would have some confidence to suggest to a new believer or new arrival. Not so today. Today in Boston there are many, many healthy and vibrant churches to choose from all across the city. Our understanding of the Quiet Revival is not only a matter of statistics, it is our actual experience as our work puts us in a position to constantly interact with church leaders representing many different communities in the city.

It appears from this vantage point that the rate of church planting in Boston continues to be robust as we approach the 50-year mark for the Quiet Revival. We are looking forward with excitement to see what the new numbers are when the 2014 church survey is complete. It also appears from the many evidences gained through our relational networks across Boston that these additional indicators of the Quiet Revival also continue to grow stronger.

Notes

(If the resources below are not linked, it is because in 2016 we migrated from EGC’s old website to a new site, and not all documents and pages have been posted. As we are able, we will repost articles from the Emmanuel Research Review and link those that are mentioned below. If you have questions, please click the Take Action button below and Contact Rudy Mitchell, Senior Researcher.)

1We have written in previous issues about these surveys. See the following editions of the Emmanuel Research Review: No. 18, June 2006, Surveying Churches; No. 19, July/August 2006, Surveying Churches II: The Changing Church System in Boston; No. 21, October 2006, Surveying Churches III: Facts that Tell a Story.

2Daman, Steve. “1969-2005: Four Decades of Church Surveys.” Inside EGC 12, no. 5 (September-October, 2005): p. 4.

3Mitchell, Rudy. “A Portrait of Boston’s Churches.” in Hall, Douglas, Rudy Mitchell, and Jeffrey Bass. Christianity in Boston: A Series of Monographs & Case Studies on the Vitality of the Church in Boston. Boston, MA, U.S.A: Emmanuel Gospel Center, 1993. p. B-14.

4We estimate the number of churches in 1965 was 318, based on information derived from Polk’s Boston City Directory (https://archive.org/details/bostondirectoryi11965bost) for that year and adjusted to include only Christian churches. In 1965, many small, newer African American churches were thriving in low-cost storefronts and many of the smaller neighborhood mainline churches had not yet closed or moved out of the city (but many soon would). While there were not yet many new immigrant churches, the city's African American population was growing very significantly and also expanding into new neighborhoods where new congregations were needed.

5Hall, Douglas A., from the Foreword to the section entitled “A Portrait of Boston’s Churches” by Rudy Mitchell, in Hall, Douglas, Rudy Mitchell, and Jeffrey Bass. Christianity in Boston: A Series of Monographs & Case Studies on the Vitality of the Church in Boston. Boston, MA, U.S.A: Emmanuel Gospel Center, 1993. p. B-1.

6Daman, Steve. “EGC’s Research Uncovers the Quiet Revival.” Inside EGC 20, no. 4 (November-December 2013): p. 2.

7Ibid.

8Emmanuel Research Review, No. 60, November 2010, There’s Gold in the City.

9Keller, Tim. “Questions for Sleepy and Nominal Christians.” Worldview Church Digest, March 13, 2013. Web. Accessed January 27, 2014.

10Bebbington, D W. Victorian Religious Revivals: Culture and Piety in Local and Global Contexts. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012. p.3.

11Ripken, Nik. personal website. n.d. http://www.nikripken.com/

12Miranda, Roberto. “A vision for revival in New England.” April 7, 2006. Web.

13Daman, Steve. “The City Gives Birth to a Seminary.” Africanus Journal Vol. 8, No. 1, April 2016, Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, Center for Urban Ministerial Education. p. 33.

14We wrote about the difficulties national organizations have in coming up with that figure in a previous edition of the Review: No. 88, April 2013, “Perspectives on Boston Church Statistics: Is Greater Boston Really Only 2% Evangelical?”

15Dilley, Andrea Palpant. “The World the Missionaries Made.” Christianity Today 58, no. 1 (January/February 2014): p. 34. Web. Accessed: January 30, 2014. Dilley quotes Robert at the end of her article on the impact some 19th century missionaries had shaping culture in positive ways.

16A number of educational opportunities for church leaders are listed in the Review, No. 70, Sept 2011, “Urban Ministry Training Programs & Centers.”

TAKE ACTION

We have mentioned throughout this article that we would welcome scholars, researchers, and interns who could help contribute to our understanding of this movement in Boston.

Note: Some document links might connect to resources that are no longer active.

Emmanuel Research Review

The Emmanuel Research Review (2004-2014) was a digital journal from the Emmanuel Gospel Center’s Applied Research department that featured articles, papers, resources, and information designed to be a resource for urban pastors, leaders and community members in their efforts to serve their communities effectively. Ninety-five issues of The Review were published during its ten-year run from 2004 to 2014. On this page we offer a list of all issues published, and links to those that have been reposted to this new site.

WHAT IS IT?

The Emmanuel Research Review (2004 - 2014) was a digital journal from the Emmanuel Gospel Center’s Applied Research department. The Review featured regular articles, papers, and other resources to support urban pastors, leaders and community members in their efforts to serve their communities effectively. Ninety-five issues of The Review were published during its ten-year run from 2004 to 2014.

THEN AND NOW

When EGC’s Applied Research and Consulting department began a comprehensive reorganization in 2014, we discontinued publication until we were in a better position to produce new materials that would be even more effective. In 2016, when we launched a new website, the ERR archive was no longer available. Now we are working to repost some of the best from the past while we continue producing new resources addressing a wide range of urban issues.

LIST OF PUBLISHED ISSUES

2014

Issue No. 95 — March 2014 — Knowing Your Neighborhood: An Update of Boston’s South End Churches. (EGC reassessed the status of churches in our own neighborhood, Boston’s South End.)

Issue No. 94 — December 2013 - January 2014 — Understanding Boston’s Quiet Revival. (Steve Daman, Senior Writer, EGC, offers questions and discussion that lead toward a working definition and overview of “the Quiet Revival.”)

2013

Issue No. 93 — October-November 2013 — Mapping A Systemic Understanding of Homelessness for Effective Church Engagement. (EGC’s Starlight Ministries shares a homelessness system map for Boston and suggestions as to how churches can more effectively engage and impact homelessness in their communities.)

Issue No. 92 — September 2013 — “Why Cities Matter” and “Reaching for the New Jerusalem,” Books by Boston Area Authors. (Reviews of: Why Cities Matter: To God, the Culture, and the Church, by Stephen T. Um & Justin Buzzard, and Reaching for the New Jerusalem: A Biblical and Theological Framework for the City, edited by Seong Hyun Park, Aída Besançon Spencer, & William David Spencer.)

Issue No. 91 — July-August 2013 — Grove Hall Neighborhood Study. (Story and statistics on many facets of life in one Boston neighborhood.)

Issue No. 90 — June 2013 — Hidden Treasures of the Kingdom Uncovered. Celebrating Ministries to the Nations: A Manual for Organizing and Planning an Event in Your City. (Rev. Dr. Gregg Detwiler, Director of Intercultural Ministries, EGC, and Dr. Bianca Duemling, Assistant Director of Intercultural Ministries, describe a ministry event and the journey they pursued to pull it together.)

Issue No. 89 — May 2013 — 2013 Emmanuel Applied Research Award: Student Recipients. (Excerpts from the award paper, “Cambridge City-Wide Church Collaborative Cooperates to Meet Community Needs,” by Megan Footit, and abstracts from the three runners-up.)

Issue No. 88 — April 2013 — Perspectives on Boston Church Statistics: Is Boston Really Only 2% Evangelical? (Rudy Mitchell, Senior Researcher, EGC, evaluates the sources, accuracy, limitations, and weakness of some commonly used church statistics, especially with regard to their application in Boston.)

Issue No. 87 — March 2013 — Christian Engagement with Muslims in the United States. (Rev. Dr. Gregg Detwiler, Director of Intercultural Ministries at EGC, hosts a video conversation on Christian Engagement with Muslims in the U.S. Panelists: Dave Kimball, Minister-at-Large for Christian–Muslim Relations, EGC; Nathan Elmore, Program Coordinator & Consultant for Christian-Muslim Relations, Peace Catalyst International; and Paul Biswas, Pastor, International Community Church – Boston.)

Issue No. 86 — February 2013 — The Vital Signs of a Living System Ministry. (Dr. Douglas A. Hall, President of EGC and author of The Cat and the Toaster: Living System Ministry in a Technological Age, shares how Living System Ministry principles serve as vital signs which can guide our understanding and practice of leadership in urban ministry.)

2012

Issue No. 85 — December 2012–January 2013 — “Toward A More Adequate Mission Speak” and Other Resources by Ralph Kee. (An introduction to five booklets by Boston-based church planter and animator of the Greater Boston Church Planting Collaborative, Rev. Ralph Kee.)

Issue No. 84 — November 2012 — The Boston Education Collaborative’s Partnership with Boston Public Schools. (History and highlights of recent collaboration between EGC’s Boston Education Collaborative and the Boston Public Schools Faith-Based Partnerships in building church-school partnerships; and details on the BEC’s “Reflection and Learning Sessions” that provide support for Christian leaders working with students.)

Issue No. 83 — October 2012 — Churches in Boston’s Neighborhood of Mattapan. (Erik Nordbye, Research Associate of EGC, studied and analyzed data on 65 Christian churches in Boston’s diverse Mattapan neighborhood.)

Issue No. 82 — September 2012 — Christian Churches in Somerville, Mass. (A profile of 46 Christian churches in the city of Somerville, Mass.)

Issue No. 81 — August 2012 — Christian Churches in North Dorchester of Boston, Mass. (Hanno van der Bijl, Research Associate at EGC, studied the diverse and vital expressions of the church in the North Dorchester neighborhood of Boston. The report also documents the slow growth in the number of churches over the last 25 years.)

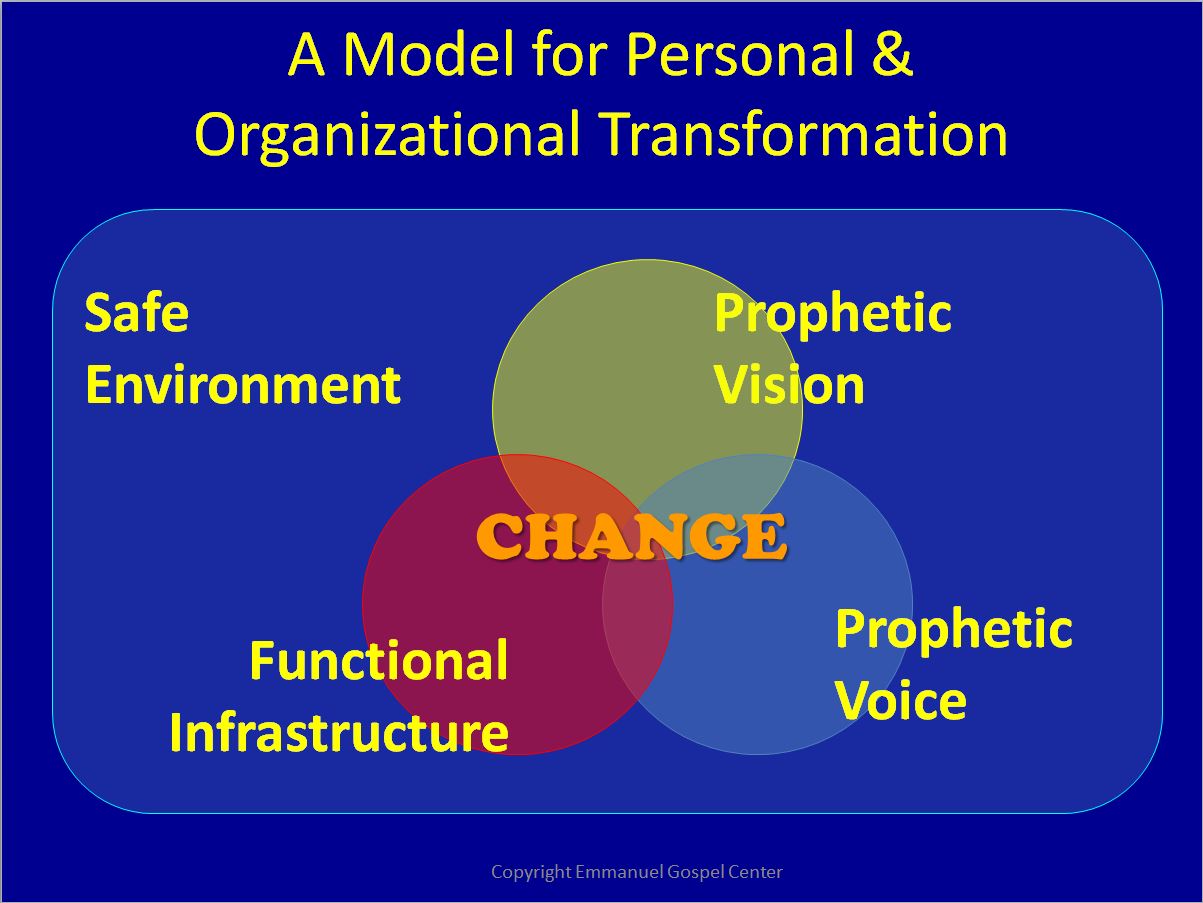

Issue No. 80 — July 2012 — Developing Safe Environments for Learning and Transformation. (Rev. Dr. Gregg Detwiler, Director of Intercultural Ministries, EGC, shares from his experience regarding “a model for personal and organizational transformation” while underscoring the importance of creating a safe environment.)

Issue No. 79 — June 2012 — Emmanuel Applied Research Award: Student Recipients. (The 2012 award paper, “Miriam’s House Ministries and The Melville Park Micro-enterprise Experiment,” by Jim Hartman, is presented in its entirety, and there are links to the executive summaries of the three runners up.)

Issue No. 78 — May 2012 — The Rise of the Global South: The Decline of Western Christendom and the Rise of Majority World Christianity, by Elijah J. F. Kim. (An introduction to the above named book by Elijah J. F. Kim, former Director of the Vitality Project, EGC. Dr. Kim says “the center of gravity of the Christian faith has shifted from the West to the non-West.”)

Issue No. 77 — April 2012 — The Black Church and Hip Hop Culture & Under One Steeple, Books by Boston Area Authors. (Reviews of The Black Church and Hip Hop Culture: Toward Bridging the Generational Divide, edited by Emmett G. Price III, and Under One Steeple: Multiple Congregations Sharing More Than Just Space, by Lorraine Cleaves Anderson, former pastoral of International Community Church in Allston.)

Issue No. 76 — March 2012 — Hartford Survey Project: Understanding Service Needs and Opportunities. (Jessica Sanderson of Urban Alliance shares about the purpose, process, analysis, findings and application of the Hartford Survey.)

Issue No. 75 — February 2012 — Behind the Scenes: Setting the Stage for Conversation about the Church in New England. (Video series from Brandt Gillespie of PrayTV and Dr. Roberto Miranda of Congregación León de Judá in Boston about the church in New England.)

Issue No. 74 — January 2012 — Shared Worship Space, an Urban Challenge and a Kingdom Opportunity. (Dr. Bianca Duemling, Assistant Director, Intercultural Ministries, EGC, outlines the challenges of churches sharing space.)

2011

Issue No. 73 — December 2011 — Let’s Do It! Multiplying Churches in Boston Now. (Rev. Ralph A. Kee, animator of the Greater Boston Church Planting Collaborative, connects first century practices with 21st century potentialities for Boston.)

Issue No. 72 — November 2011 — Crossing Beyond the Organization Threshold. (Dr. Douglas A. Hall, President, EGC, shares thoughts on the limitations of organization and the danger of having it become our ministry’s focus, and how we can use organization and technology appropriately to benefit a living system.)

Issue No. 71 — October 2011 — Human Trafficking: The Abolitionist Network. (Sarah Durfey, director, the Abolitionist Network, an emerging ministry of EGC, talks about how we can address human trafficking using a Living System Ministry approach.)

Issue No. 70 — September 2011 — Urban Ministry Training in Metro Boston. (Hanno van der Bijl, Research Associate, EGC, offers a brief introduction on urban ministry training in Metro Boston, the Urban Ministry Training Directory, a brief analysis, and a list of related resources.)

Issue No. 69 — August 2011 — The Diverse Leadership Project. (Dr. Bianca Duemling, Assistant Director, Intercultural Ministries, EGC, gives a brief overview of the project which seeks to better understand leadership development, styles, and priorities within various ethnic church communities. Includes interviews with six New England church leaders in five different ethnic contexts.)

Issue No. 68 — July 2011 — Metro Boston Collegiate Ministry Project: Focus Group/Learning Team Report. (The story of how the collaborative project began, initial group assumptions, and the “hexagonning” exercise that engaged 50 local leaders in a shared learning process to understand local college ministry.)

Issue No. 67 — June 2011 — Metro Boston Collegiate Ministry Project: Student Enrollment Report. (Who attends Boston’s colleges? This report examines student enrollment profiles for each of the 35 schools in Metro Boston.)

Issue No. 66 — May 2011 — Emmanuel Applied Research Award: Student Recipients. (The 2011 award paper, “Faith-Based Healthcare for the Underserved of Lawrence, MA: A Pilot Project,” by Stephen Ko, is presented in its entirety.)

Issue No. 65 — April 2011 — Boston Education Collaborative Church Survey Report. (How Boston-area churches are engaged in education, what areas of programming they are interested in further developing, and what resources are needed for them to become more involved in education.)

Issue No. 64 — March 2011 — Connecting the Disconnected: A Survey of Youth and Young Adults in Grove Hall. (An April, 2010, report on out-of-work and out-of-school young adults ages 16-24 in the Grove Hall area of Boston, and an interview with Ra’Shaun Nalls and Martin Booth of Project R.I.G.H.T., who share the story behind the study.)

Issue No. 63 — February 2011 — Youth Violence Systems Project Special Edition Review. (An overview of the community-based process that is at the heart of the Youth Violence Systems Project (YVSP), the YVSP strategy lab, the reason why we haven’t solved the gang violence problem, and what we are learning.)

Issue No. 62 — January 2011 — The Urban Apostolic Task. (In this issue, Rev. Ralph Kee, animator, Greater Boston Church Planting Collaborative, illuminates the vision, practical instruction, and urgency of an apostolic ministry that engages the entire church in “new-world building movements.”)

2010

Issue No. 59 — September/October 2010 — A New Kind of Learning: Contextualized Theological Education Models. (Dr. Alvin Padilla, Dean of Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary’s Center for Urban Ministerial Education, Boston, considers the challenge theological schools have best serving the needs of diverse cultures in cities today.)

2008

Issue No. 41 — September/October 2008 — Urban Youth Mentoring. (Rudy Mitchell, Senior Researcher, summarizes his research findings regarding various practical aspects on mentoring youth in an urban context. Rudy’s research draws from both secular and faith-based sources regarding preparation, planning, recruiting, screening, training, matching, support, monitoring, closure, and evaluation of youth mentoring programs.)

More to come!

This is just a start. Stay tuned for more back issues listed and posted on this site. Or check out the Wayback Machine link below for another way to find back issues.

Learn More / Take Action

Questions? Is there something missing from our archives that you need? If you have questions or comments about the Emmanuel Research Review, don’t hesitate to be in touch. We would love to hear from you!

Researchers may find additional back issues by searching the internet “Wayback Machine” here:

Grove Hall Neighborhood Study

This summary of a larger study offers both story and statistics on life and culture in one Boston neighborhood. Following a brief history of the area, the study offers data on racial trends, economy, housing, education and more.

Resources for the urban pastor and community leader published by Emmanuel Gospel Center, Boston

Emmanuel Research Review reprint

Issue No. 91 — July-August 2013

Introduced by Brian Corcoran, managing editor

Neighborhood studies reveal dynamics and principles which reflect the unique shape—culturally, geographically, and socially, for example—of a given place. By highlighting neighborhood-specific histories, heroes, and innovations, we can add story to statistics, and help complement, interrelate, and animate data in ways that better inform and inspire the development of community responses to community challenges. The Emmanuel Gospel Center has produced various neighborhood studies to this end. In recent years, we have supported the Youth Violence Systems Project by conducting research on a half dozen neighborhoods that are known to have had a history of youth violence. These studies help provide a wider framework for viewing each neighborhood as they touch on many aspects of what makes that particular neighborhood unique.

The Grove Hall Neighborhood Study, Second Edition (2013) offers both story and statistics on many facets of life in this one Boston neighborhood. Following a brief history of the immediate area, the study offers data on racial trends; facts about the current population including, for example, the breakdown of ages of the residents and how they compare with other areas; and facts about the economy, housing, and education. There are also updated, annotated directories of the neighborhood’s churches, schools, and agencies including those agencies particularly concerned with violence prevention and public safety. Fourteen tables, nine new graphs designed by Jonathan Parker, four maps, over a dozen images, and an extensive bibliography help tell the story.

In this issue of the Emmanuel Research Review, we offer excerpts from the Grove Hall study with bullet points and graphics. The complete report can be viewed or downloaded HERE as a pdf file.

Understanding the Grove Hall Neighborhood

by Rudy Mitchell, Senior Researcher, Emmanuel Gospel Center

About the Grove Hall Neighborhood Study

Continuing in its commitment to foster stronger communication, agreement, and cooperation around a community-wide response to youth violence in Boston, the Emmanuel Gospel Center (EGC) has recently released an updated research study on Boston’s Grove Hall neighborhood.

The Grove Hall Neighborhood Study, Second Edition, copyright © 2013 Emmanuel Gospel Center, was written and researched by Rudy Mitchell, senior researcher at EGC, and produced by the Youth Violence Systems Project, a partnership between EGC and the Black Ministerial Alliance of Greater Boston. A first edition was released in 2009 and titled Grove Hall Neighborhood Briefing Document. As the first edition was produced prior to the 2010 U.S. Census, much of the information was based on the 2000 Census. By returning to Grove Hall now, not only is EGC able to study the latest numbers, but changes over the past decade may indicate either new concerns or evidences of progress.

This neighborhood study is one of six Boston neighborhood studies. The others in this series are: Uphams Corner (2008), Bowdoin-Geneva (2009), South End & Lower Roxbury (2009), Greater Dudley (2010), and Morton-Norfolk (2010).